Notice

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

Ver. 2501112501118

| 일 | 월 | 화 | 수 | 목 | 금 | 토 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 |

| 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 |

| 30 | 31 |

Tags

- 가섭결경

- 마하반야바라밀경

- 대지도론

- 증일아함경

- 마명

- Japan

- 유마힐소설경

- 금강삼매경론

- 대반열반경

- 정법화경

- 유가사지론

- 장아함경

- 종경록

- 근본설일체유부비나야

- 유마경

- 대승기신론

- 대방광불화엄경60권본

- 중아함경

- 백유경

- 원각경

- 무량의경

- 대반야바라밀다경

- 반야심경

- 아미타불

- 마하승기율

- 묘법연화경

- 수능엄경

- 잡아함경

- 대방광불화엄경

- 방광반야경

Archives

- Since

- 2551.04.04 00:39

- ™The Realization of The Good & The Right In Wisdom & Nirvāṇa Happiness, 善現智福

- ॐ मणि पद्मे हूँ

불교진리와실천

달마_cf 본문

>>>>

다르마 (불교)

위키백과, 우리 모두의 백과사전.

| 불교 |

|---|

|

| 교의와 용어[보이기] |

| 인물[보이기] |

| 역사와 종파[보이기] |

| 경전[보이기] |

| 성지[보이기] |

| 지역별 불교[보이기] |

| v t e |

불교에서 법은 교법, 최고의 진리, 법칙, 도리, 존재, 실체, 모든 존재(일체법) 등 다양한 뜻이 있다.[1]

불교의 불법승(佛法僧) 3보(三寶) 가운데 법보(法寶)라고 할 때

법은 교법(敎法) · 이법(理法) · 행법(行法) · 과법(果法)의 4법을 뜻한다.

이 가운데 교법(敎法)은 좁은 의미에서 고타마 붓다의 가르침을 뜻하고,

넓은 의미에서 3세제불(三世諸佛)의 가르침

즉 모든 부처 즉 깨달은 자의 가르침 또는 불교 경전들에 나타난 가르침 전체를 뜻한다.[2]

이법(理法)은 교법이 가리키고 해설하고 있는 진리를 뜻하며,

행법(行法)은 이법 즉 진리를 성취하게 하는 계(戒) · 정(定) · 혜(慧) 등의 방편 또는 수행을 뜻하며,

과법(果法)은 행법이 원만해졌을 때 증득되는 이법 즉 진리 즉 열반을 뜻한다.[3][4]

따라서, 법보(法寶)의 법은 불교의 교의(가르침) · 수행(도리, 방편) · 진리를 모두 뜻한다.

부파불교의 아비달마와 대승불교의 유식학과

불교 일반에서 일체법(一切法), 법상(法相) 또는 제법분별(諸法分別)이라고 할 때의 법은

존재 또는 실체를 뜻하며,

주로 현상 세계의 존재 즉 유위법을 뜻한다.

그리고 이러한 존재 또는 실체 즉 법의 본질적 성질을

자성(自性) 또는 자상(自相)이라 한다.

이에 비해 법성(法性)이라고 할 때의 법은

진리 즉 무위법의 진여(眞如)를 뜻하며

법성을 다른 말로는 진성(眞性)이라고도 한다.[5][6]

목차

1정의1.1법

1.2일체법·만법·제법

1.3임지자성 궤생물해

2분류2.1유위법과 무위법

2.2유루법과 무루법

2.3오온

2.4십이처

2.5십팔계

2.6오위칠십오법

2.7오위백법

3같이 보기

4참고 문헌

5각주

정의[■편집]

법[■편집]

법의 인도에 있어서의 기원은 오래된 것으로서

베다에서는 신적 의지(神的意志)에 대해 인간 편에 서서 인간생활에 질서를 부여하는 것이라는 의미로 사용된 이래

오늘에 이르기까지 일반적으로 최고의 진리, 혹은 종교적 규범, 사회 규범(법률 · 제도 · 관습),

행위적 규범(윤리 · 도덕) 등

넓은 범위에 걸친 규범이라는 의미로 사용되고 있다.[1]

불교에서도 법은 그 뜻이 매우 복잡하며

다음과 같이 여러 가지 뜻으로 사용되고 있다.[1]

교법: 교설(敎說)이나 성전(聖典)

최고의 진리: 깨달음의 내용

법칙: 일체의 현실 존재로 하여금 현재의 상태로 존재케 하고 있는 법칙과 기준

도리: 인간이 실천하여 생활해야 할 도리 · 도(道) 또는 규정[7]

존재, 실체: 객관적으로 독립된 실체 또는 존재[8]

모든 존재(일체법): 법(법칙)에 의해서 지탱되고 있는 유형 · 무형, 심적 · 물적의 일체 존재(存在: 현상), 즉 의식의 대상이 되는 모든 것

일체법·만법·제법[■편집]

일체법(一切法) · 만법(萬法) 또는 제법(諸法)은

모든 법 즉 '일체(一切)의 존재[法]' 즉 '모든 존재[法]'를 뜻하는 낱말이다.[1] 줄여서 일체(一切)라고도 한다.

법(法)이라는 낱말은 모든 존재(일체법)를 뜻하는 경우로도 사용되는데,

이와 같이 법을 일체의 존재 또는 모든 존재라고 보는 견해는

인도사상(印度思想) 일반에서는 볼 수 없는 불교 독자의 것이며

법에 관한 다방면의 연구가 불교의 중요한 과제로 되어 있다.[1]

특히, 원시불교에 이은 부파불교의 시대에서는 모든 존재(일체법)를 분석하여

고집멸도의 사성제를 뚜렷히 밝히는 작업이 크게 일어났으며,

이러한 분석법은 후대의 대승불교의 유가유식파의 유식론에도 큰 영향을 끼쳤다.

임지자성 궤생물해[■편집]

법(法)에는 객관적으로 독립된 실체 또는 존재라는 의미가 있는데,[9]

임지자성 궤생물해(任持自性 軌生物解)는

이러한 의미의 법을 정의할 때 흔히 사용되는 문구이다.

중국 법상종의 규기(窺基)는

《성유식론술기(成唯識論述記)》에서 법(法)에 대해 다음과 같이 정의하고 있는데,

이 진술을 더 간단히 요약하여 "임지자성 궤생물해(任持自性 軌生物解)"라고 한다.[10]

이 정의는 대승불교의 유식유가행파의 법(法)에 대한 정의라고 할 수 있다.[10]

法謂軌持。軌謂軌範可生物解。持謂住持不捨自相。

법(法)은 궤지(軌持)를 말한다.

궤(軌)는 [해당 사물이 지닌] 궤범이 [해당] 사물에 대한 앎[解: 인식, 요해, 요별, 지식]을 낼 수 있게 한다는 것을 말한다.

지(持)는 [해당 사물이] 자상(自相)을 지니고 있어서 잃어버리지 않는 것을 말한다.

— 규기 조. 《성유식론술기(成唯識論述記)》, 제1권, T43, p. 239. 한문본

즉, 임지자성(任持自性)은 자신만의 자성(自性) 또는 자상(自相), 즉 본질적 성질을 지니고 있다는 뜻이고,

궤생물해(軌生物解)는 해당 사물에 대한 앎[解, 인식, 요해, 요별, 지식]을 낳게 하는 궤범이라는 뜻이다.[11]

궤범은 사물과 사물 사이에 작용하는 규범, 즉 법칙적 관계를 뜻하는데,[10]

'궤생물해'는 해당 사물(법)이 다른 사물(법)들에 대해 가지는 법칙적 관계,

즉 본질적 작용이 해당 사물(법)을 앎[解]에 있어서

결정적인 역할을 한다는 것을 말한다.

예를 들어, 5온 중의 하나인 수온, 즉 마음작용 중의 하나인 수(受)는

고수(苦受) · 낙수(樂受) · 불고불락수(不苦不樂受)의 3수(三受)로 나뉘는데,

3수는 다음과 같이 다른 마음작용인 촉(觸)과 욕(欲)과의 관계에서 파악할 때

아주 명료하게 이해된다.

云何受蘊。謂三領納。一苦二樂三不苦不樂。

樂謂滅時有和合欲。

苦謂生時有乖離欲。

不苦不樂謂無二欲。

수온(受蘊)이란 무엇인가? [지각대상에 대한] 3가지의 느낌[領納, 지각]을 말하는데,

첫 번째는 괴롭다는 느낌[苦受]이고,

두 번째는 즐겁다는 느낌[樂受]이고,

세 번째는 괴롭지도 즐겁지도 않다는 느낌[不苦不樂受]이다.

즐겁다는 느낌[樂受]이란 [그 지각대상이] 사라질 때

[즉, 지각대상과 헤어질 때, 그것과] 다시 만나고 싶어하는 욕구[和合欲]가 있는 것을 말한다.

괴롭다는 느낌[苦受]이란 [그 지각대상이] 생겨날 때

[즉, 지각대상과 만날 때, 그것과] 떨어지고 싶어하는 욕구[乖離欲]가 있는 것을 말한다.

괴롭지도 즐겁지도 않다는 느낌[不苦不樂受]이란

이들 2가지 욕구[欲]가 없는 것을 말한다.

— 세친 조, 현장 한역. 《대승오온론》, T31, p. 848. 한문본

즉, 법을 '임지자성 궤생물해(任持自性 軌生物解)'라고 정의하는 것은,

법은 자기만의 자성 또는 자상을 지니고 있어서

그 자성 또는 자상은 해당 법에 대한 앎[解, 인식, 요해, 요별, 지식]의 궤범이 되어

해당 법을 종합적으로 인식할 수 있게 한다는 것이며,

또한 이러한 사물 또는 존재를 법(法)이라 한다는 것이다.[11]

분류[■편집]

초기불교 이래 불교에서는 모든 존재(諸法 또는 一切)를 분석함에 있어

일반적으로 5온(五蘊), 12처(十二處) 또는 18계(十八界)의 세 분류법으로 분석하였다.

아비달마에 의하면, 모든 존재를 분석함에 있어

이러한 세 가지 분류법이 있는 이유는

가르침을 듣는 사람들의 근기에 상근기 · 중근기 · 하근기의 세 가지 유형이 있기 때문이다.

상근기에게는 5온을,

중근기에게는 12처를,

하근기에게는 18계를 설하였다.[12]

부파불교의 설일체유부에서는

이러한 5온 · 12처 · 18계의 분류방식을 더욱 발전시켜

모든 존재를

색법(色法, 11가지),

심법(心法, 1가지),

심소법(心所法, 46가지),

불상응행법(不相應行法, 14가지),

무위법(無爲法, 3가지)의 5그룹의 75가지 법으로 분류하였는데,

이를 5위 75법(五位七十五法)이라 한다.[13]

대승불교의 유식유가행파와 중국의 법상종에서는,

마찬가지로 5온 · 12처 · 18계의 분류방식을 더욱 발전시켜,

모든 존재를

심법(心法, 8가지) ·

심소법(心所法, 51가지) ·

색법(色法, 11가지) ·

심불상응행법(心不相應行法, 24가지) ·

무위법(無爲法, 6가지)의 5그룹의 100가지 법으로 분류하였는데,

이를 5위 100법(五位百法)이라 한다.[14][15]

유위법과 무위법[■편집]

유루법과 무루법[■편집]

오온[■편집]

십이처[■편집]

십팔계[■편집]

오위칠십오법[■편집]

오위백법[■편집]

같이 보기[■편집]

삼귀의

불보

승보

5온

12처

18계

5위 75법

5위 100법

22문

제문분별

참고 문헌[■편집]

권오민 (2003). 《아비달마불교》. 민족사.

세친 지음, 현장 한역, 권오민 번역. 《아비달마구사론》. 한글대장경 검색시스템 - 전자불전연구소 / 동국역경원. |title=에 외부 링크가 있음 (도움말)

황욱 (1999). 《무착[Asaṅga]의 유식학설 연구》. 동국대학원 불교학과 박사학위논문.

각주[■편집]

↑ 이동:가 나 다 라 마 바 종교·철학 > 세계의 종교 > 불 교 > 불교의 사상 > 근본불교의 사상 > 법, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

↑ 운허, "敎法(교법)". 2013년 1월 13일에 확인

"敎法(교법): 4법(法)의 하나. 한 종파의 교리를 언어ㆍ문자로써 설명하는 교설."

↑ 운허, "四法(사법)". 2013년 1월 13일에 확인

"四法(사법): 불ㆍ법ㆍ승 3보 중에서 법보를 나누어 교법(敎法)ㆍ이법(理法)ㆍ행법(行法)ㆍ과법(果法)으로 한 것. 교(敎)는 부처님의 말로써 설한 교법. 이(理)는 교법 중에 포함된 주요한 도리. 행(行)은 닦아서 증득할 행법(行法), 곧 계ㆍ정ㆍ혜 3학(學)등. 과(果)는 최후에 도달할 이상경(理想境)인 열반."

↑ 星雲, "四法". 2013년 1월 13일에 확인

"四法: (一)指三寶中之法寶。有教法、理法、行法、果法四種,故又稱四法寶。據大乘本生心地觀經卷二、大乘法苑義林章卷六本等所舉:(一)教法,三世諸佛之言教。(二)理法,教法所詮釋之義理。(三)行法,依理法而起行之戒、定、慧等能修之因位修行。(四)果法,修行圓滿,所得能證之無為涅槃證果。諸佛即以此四法引導眾生,出離生死苦海而至彼岸,達於涅槃解脫之境界。又諸佛亦依此四法而修行,斷一切障而成菩提。〔觀無量壽佛經義疏卷中(慧遠)、成唯識論述記卷一本、華嚴經探玄記卷三〕 "

↑ 운허, "法性(법성)". 2013년 1월 13일에 확인

"法性(법성): 【범】Dharmatā 항상 변하지 않는 법의 법다운 성(性). 모든 법의 체성(體性). 곧 만유의 본체. 진여(眞如)ㆍ실상(實相)ㆍ법계(法界) 등이라고도 함."

↑ 星雲, "法性". 2013년 1월 13일에 확인

"法性: 梵語 dharmatā,巴利語 dhammatā。指諸法之真實體性。亦即宇宙一切現象所具有之真實不變之本性。又作真如法性、真法性、真性。又為真如之異稱。法性乃萬法之本,故又作法本。大智度論卷三十二即以一切法之總相、別相同歸於法性,謂諸法有各各相(即現象之差別相)與實相。所謂各各相,例如蠟炙火溶,頓失以前之相,以其為不固定者,故分別求之而不可得;不可得故空(無自性),即說空為諸法之實相。對一切差別相而言,因其自性是空,故皆為同一,稱之為「如」。一切相同歸於空,故稱空為法性。又如黃石之中具有金之性質,一切世間法中皆具涅槃之法性,故說此諸法本然之實性為法性,此與圓覺經所謂「眾生、國土同一法性」同義。釋尊曾於大寶積經卷五十二開示諸法實性之義,謂法性無有變異,無有增益,無作無不作;復於一切處通照平等,於諸平等中善住平等,不平等中善住平等,於諸平等不平等中妙善平等;又謂法性無有分別,無有所緣,於一切法能證得究竟體相。故若有依趣法性者,則諸法性無不依趣。一般對法性與如來藏加以區別,即廣指一切法之實相為法性,然亦有主張法性與如來藏同義之說。如大般若經卷五六九法性品說如來之法性與大乘止觀法門卷一等即屬此說。〔大品般若經卷二十一、菩薩地持經卷一、成唯識論卷二、大智度論卷二十八、大乘玄論卷三〕(參閱「真如」、「真理」)"

↑ 동양사상 > 동양의 사상 > 인도의 사상 > 불교 > 원시불교의 사상, 《글로벌 세계 대백과사전》

↑ 세친 지음, 현장 한역, 권오민 번역. 《아비달마구사론》 제 1 권, 1. 분별계품(分別界品) ①[깨진 링크(과거 내용 찾기)]. 한글대장경 검색시스템 - 전자불전연구소 / 동국역경원. 11 / 1397 쪽의 역자주 21). 2012년 8월 27일에 확인.

↑ 세친 지음, 현장 한역, 권오민 번역, 11 / 1397쪽.

↑ 이동:가 나 다 황욱 1999, 26쪽.

↑ 이동:가 나 세친 지음, 현장 한역, 권오민 번역, 4 / 1397쪽.

↑ 권오민 2003, 49-56쪽.

↑ 권오민 2003, 56쪽.

↑ 《성유식론(成唯識論)》 제7권; 《대승아비달마잡집론(大乘阿毗達磨雜集論)》제2권;《대승백법명문론소(大乘百法明門論疎)》; 《대승백법명문론해(大乘百法明門論解)》

↑ (중국어) "五位百法" "五位百法"[깨진 링크(과거 내용 찾기)], 《佛光大辭典(불광대사전)》. 3판. 2012년 8월 26일에 확인.

| 펼치기v t e |

|---|

| 펼치기v t e |

|---|

| 펼치기v t e |

|---|

| 펼치기v t e |

|---|

| 펼치기v t e |

|---|

| 펼치기v t e |

|---|

분류: 불교 용어

힌두교 용어

불교 교의

>>>

Dharma

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Dharma (Buddhism))

This article is about the concept found in Indian religions. For other uses, see Dharma (disambiguation).

Dharma

Rituals and rites of passage[1]

Yoga, personal behaviours[2]

Virtues such as Ahimsa (non-violence)[3]

Law and justice[4]

Sannyasa and stages of life[5]

Duties, such as learning from teachers[6]

Dharma (/ˈdɑːrmə/;[7] Sanskrit: धर्म, romanized: dharma, pronounced [dʱɐrmɐ] (

In Hinduism, dharma signifies behaviours that are considered to be in accord with Ṛta, the order that makes life and universe possible,[10][note 1] and includes duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and "right way of living".[11] In Buddhism, dharma means "cosmic law and order",[10][12] as applied to the teachings of Buddha [10][12] and can be applied to mental constructs or what is cognised by the mind.[12] In Buddhist philosophy, dhamma/dharma is also the term for "phenomena".[13][note 2] Dharma in Jainism refers to the teachings of tirthankara (Jina)[10] and the body of doctrine pertaining to the purification and moral transformation of human beings. For Sikhs, dharma means the path of righteousness and proper religious practice.[14]

The concept of dharma was already in use in the historical Vedic religion, and its meaning and conceptual scope has evolved over several millennia.[15] The ancient Tamil moral text of Tirukkural is solely based on aṟam, the Tamil term for dharma.[16] The antonym of dharma is adharma.

Contents

1Etymology

2Definition

3History3.1Eusebeia and dharma

3.2Rta, maya and dharma

4Hinduism4.1In Vedas and Upanishads

4.2In the Epics

4.3According to 4th century Vatsyayana

4.4According to Patanjali Yoga

4.5Sources

4.6Dharma, life stages and social stratification

4.7Dharma and poverty

4.8Dharma and law

5Buddhism5.1Buddha's teachings

5.2Chan Buddhism

5.3Therevada Buddhism

6Jainism6.1Dharmastikaay (Dravya)

7Sikhism

8Dharma in symbols

9See also

10Notes

11References11.1Citations

11.2Sources

12External links

Etymology[edit]

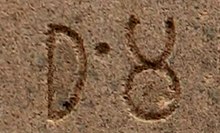

The Prakrit word "Dha-ṃ-ma"/𑀥𑀁𑀫 (Sanskrit: Dharma धर्म) in the Brahmi script, as inscribed by Emperor Ashoka in his Edicts of Ashoka (3rd century BCE).

The Classical Sanskrit noun dharma (धर्म) or the Prakrit Dhaṃma (𑀥𑀁𑀫) are a derivation from the root dhṛ, which means "to hold, maintain, keep",[note 3]. Hence, dharma holds one from falling down or falling to hell. Therefore, it takes the meaning of "what is established or firm", and hence "law". It is derived from an older Vedic Sanskrit n-stem dharman-, with a literal meaning of "bearer, supporter", in a religious sense conceived as an aspect of Rta.[18]

In the Rigveda, the word appears as an n-stem, dhárman-, with a range of meanings encompassing "something established or firm" (in the literal sense of prods or poles). Figuratively, it means "sustainer" and "supporter" (of deities). It is semantically similar to the Greek Themis ("fixed decree, statute, law").[19] In Classical Sanskrit, the noun becomes thematic: dharma-.

The word dharma derives from Proto-Indo-European root

*dʰer- ("to hold"),[20] which in Sanskrit is reflected as class-1 root[clarification needed] dhṛ. Etymologically it is related to Avestan dar- ("to hold"), Latin firmus ("steadfast, stable, powerful"), Lithuanian derė́ti ("to be suited, fit"), Lithuanian dermė ("agreement")[21] and darna ("harmony") and Old Church Slavonic drъžati ("to hold, possess").

Classical Sanskrit word dharmas would formally match with Latin o-stem firmus from Proto-Indo-European dʰer-mo-s "holding", were it not for its historical development from earlier Rigvedic n-stem.

In Classical Sanskrit, and in the Vedic Sanskrit of the Atharvaveda, the stem is thematic: dhárma- (Devanāgarī: धर्म). In Prakrit and Pāli, it is rendered dhamma. In some contemporary Indian languages and dialects it alternatively occurs as dharm.

Ancient translationsWhen the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka wanted in the 3rd century BCE to translate the word "Dharma" (he used Prakrit word Dhaṃma) into Greek and Aramaic,[22] he used the Greek word Eusebeia (εὐσέβεια, piety, spiritual maturity, or godliness) in the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription and the Kandahar Greek Edicts, and the Aramaic word Qsyt ("Truth") in the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription.[23]

Definition[edit]

Dharma is a concept of central importance in Indian philosophy and religion.[24] It has multiple meanings in Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism and Jainism.[8] It is difficult to provide a single concise definition for dharma, as the word has a long and varied history and straddles a complex set of meanings and interpretations.[25] There is no equivalent single-word synonym for dharma in western languages.[9]

There have been numerous, conflicting attempts to translate ancient Sanskrit literature with the word dharma into German, English and French. The concept, claims Paul Horsch,[26] has caused exceptional difficulties for modern commentators and translators. For example, while Grassmann's[27] translation of Rig-veda identifies seven different meanings of dharma, Karl Friedrich Geldner in his translation of the Rig-veda employs 20 different translations for dharma, including meanings such as "law", "order", "duty", "custom", "quality", and "model", among others.[26] However, the word dharma has become a widely accepted loanword in English, and is included in all modern unabridged English dictionaries.

The root of the word dharma is "dhri", which means "to support, hold, or bear". It is the thing that regulates the course of change by not participating in change, but that principle which remains constant.[28] Monier-Williams, the widely cited resource for definitions and explanation of Sanskrit words and concepts of Hinduism, offers[29] numerous definitions of the word dharma, such as that which is established or firm, steadfast decree, statute, law, practice, custom, duty, right, justice, virtue, morality, ethics, religion, religious merit, good works, nature, character, quality, property. Yet, each of these definitions is incomplete, while the combination of these translations does not convey the total sense of the word. In common parlance, dharma means "right way of living" and "path of rightness".[28]

The meaning of the word dharma depends on the context, and its meaning has evolved as ideas of Hinduism have developed through history. In the earliest texts and ancient myths of Hinduism, dharma meant cosmic law, the rules that created the universe from chaos, as well as rituals; in later Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas and the Epics, the meaning became refined, richer, and more complex, and the word was applied to diverse contexts.[15] In certain contexts, dharma designates human behaviours considered necessary for order of things in the universe, principles that prevent chaos, behaviours and action necessary to all life in nature, society, family as well as at the individual level.[10][15][30][note 1] Dharma encompasses ideas such as duty, rights, character, vocation, religion, customs and all behaviour considered appropriate, correct or morally upright.[31]

The antonym of dharma is adharma (Sanskrit: अधर्म),[32] meaning that which is "not dharma". As with dharma, the word adharma includes and implies many ideas; in common parlance, adharma means that which is against nature, immoral, unethical, wrong or unlawful.[33]

In Buddhism, dharma incorporates the teachings and doctrines of the founder of Buddhism, the Buddha.

History[edit]

According to the authoritative book History of Dharmasastra, in the hymns of the Rigveda the word dharma appears at least fifty-six times, as an adjective or noun. According to Paul Horsch,[26] the word dharma has its origin in the myths of Vedic Hinduism. The hymns of the Rig Veda claim Brahman created the universe from chaos, they hold (dhar-) the earth and sun and stars apart, they support (dhar-) the sky away and distinct from earth, and they stabilise (dhar-) the quaking mountains and plains.[26][34] The gods, mainly Indra, then deliver and hold order from disorder, harmony from chaos, stability from instability – actions recited in the Veda with the root of word dharma.[15] In hymns composed after the mythological verses, the word dharma takes expanded meaning as a cosmic principle and appears in verses independent of gods. It evolves into a concept, claims Paul Horsch,[26] that has a dynamic functional sense in Atharvaveda for example, where it becomes the cosmic law that links cause and effect through a subject. Dharma, in these ancient texts, also takes a ritual meaning. The ritual is connected to the cosmic, and "dharmani" is equated to ceremonial devotion to the principles that gods used to create order from disorder, the world from chaos.[35] Past the ritual and cosmic sense of dharma that link the current world to mythical universe, the concept extends to ethical-social sense that links human beings to each other and to other life forms. It is here that dharma as a concept of law emerges in Hinduism.[36][37]

Dharma and related words are found in the oldest Vedic literature of Hinduism, in later Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, and the Epics; the word dharma also plays a central role in the literature of other Indian religions founded later, such as Buddhism and Jainism.[15] According to Brereton,[38] Dharman occurs 63 times in Rig-veda; in addition, words related to Dharman also appear in Rig-veda, for example once as dharmakrt, 6 times as satyadharman, and once as dharmavant, 4 times as dharman and twice as dhariman.

Indo-European parallels for "Dharma" are known, but the only Iranian equivalent is Old Persian darmān "remedy", the meaning of which is rather removed from Indo-Aryan dhárman, suggesting that the word "Dharma" did not have a major role in the Indo-Iranian period, and was principally developed more recently under the Vedic tradition.[38] However, it is thought that the Daena of Zoroastrianism, also meaning the "eternal Law" or "religion", is related to Sanskrit "Dharma".[39] Ideas in parts overlapping to Dharma are found in other ancient cultures: such as Chinese Tao, Egyptian Maat, Sumerian Me.[28]

Eusebeia and dharma[edit]

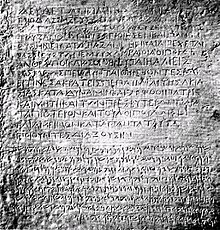

The Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription is from Indian Emperor Asoka in 258 BC, and found in Afghanistan. The inscription renders the word Dharma in Sanskrit as Eusebeia in Greek, suggesting dharma in ancient India meant spiritual maturity, devotion, piety, duty towards and reverence for human community.[40]

In the mid-20th century, an inscription of the Indian Emperor Asoka from the year 258 BC was discovered in Afghanistan, the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription. This rock inscription contains Greek and Aramaic text. According to Paul Hacker,[40] on the rock appears a Greek rendering for the Sanskrit word dharma: the word eusebeia.[40] Scholars of Hellenistic Greece explain eusebeia as a complex concept. Eusebia means not only to venerate gods, but also spiritual maturity, a reverential attitude toward life, and includes the right conduct toward one's parents, siblings and children, the right conduct between husband and wife, and the conduct between biologically unrelated people. This rock inscription, concludes Paul Hacker,[40] suggests dharma in India, about 2300 years ago, was a central concept and meant not only religious ideas, but ideas of right, of good, of one's duty toward the human community.[41]

Rta, maya and dharma[edit]

The evolving literature of Hinduism linked dharma to two other important concepts: Ṛta and Māyā. Ṛta in Vedas is the truth and cosmic principle which regulates and coordinates the operation of the universe and everything within it.[42][43] Māyā in Rig-veda and later literature means illusion, fraud, deception, magic that misleads and creates disorder,[44] thus is contrary to reality, laws and rules that establish order, predictability and harmony. Paul Horsch[26] suggests Ṛta and dharma are parallel concepts, the former being a cosmic principle, the latter being of moral social sphere; while Māyā and dharma are also correlative concepts, the former being that which corrupts law and moral life, the later being that which strengthens law and moral life.[43][45]

Day proposes dharma is a manifestation of Ṛta, but suggests Ṛta may have been subsumed into a more complex concept of dharma, as the idea developed in ancient India over time in a nonlinear manner.[46] The following verse from the Rigveda is an example where rta and dharma are linked:

O Indra, lead us on the path of Rta, on the right path over all evils...

— RV 10.133.6

Hinduism[edit]

cosmos and its parts.[28] It refers to the order and customs which make life and universe possible, and includes behaviours, rituals, rules that govern society, and ethics.[10][note 1] Hindu dharma includes the religious duties, moral rights and duties of each individual, as well as behaviours that enable social order, right conduct, and those that are virtuous.[47] Dharma, according to Van Buitenen,[48] is that which all existing beings must accept and respect to sustain harmony and order in the world. It is neither the act nor the result, but the natural laws that guide the act and create the result to prevent chaos in the world. It is innate characteristic, that makes the being what it is. It is, claims Van Buitenen, the pursuit and execution of one's nature and true calling, thus playing one's role in cosmic concert. In Hinduism, it is the dharma of the bee to make honey, of cow to give milk, of sun to radiate sunshine, of river to flow.[48] In terms of humanity, dharma is the need for, the effect of and essence of service and interconnectedness of all life.[28][40]

In its true essence, dharma means for a Hindu to "expand the mind" as the scholar Devdutt Pattnaik suggests in his treatises in Hinduism. Furthermore, it represents the direct connection between the individual and the societal phenomena that bind the society together. In the way societal phenomena affect the conscience of the individual, similarly do the actions of an individual may alter the course of the society, for better or for worse. This is been subtly echoed by the credo धर्मो धारयति प्रजा: meaning dharma is that which holds and provides support to the social construct.

In Hinduism, dharma includes two aspects – sanātana dharma, which is the overall, unchanging and abiding principals of dharma and is not subject to change, and yuga dharma, which is valid for a yuga, an epoch or age as established by Hindu tradition.

In Vedas and Upanishads[edit]

The history section of this article discusses the development of dharma concept in Vedas. This development continued in the Upanishads and later ancient scripts of Hinduism. In Upanishads, the concept of dharma continues as universal principle of law, order, harmony, and truth. It acts as the regulatory moral principle of the Universe. It is explained as law of righteousness and equated to satya (Sanskrit: सत्यं, truth),[49][50] in hymn 1.4.14 of Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, as follows:

धर्मः तस्माद्धर्मात् परं नास्त्य् अथो अबलीयान् बलीयाँसमाशँसते धर्मेण यथा राज्ञैवम् ।

यो वै स धर्मः सत्यं वै तत् तस्मात्सत्यं वदन्तमाहुर् धर्मं वदतीति धर्मं वा वदन्तँ सत्यं वदतीत्य् एतद्ध्येवैतदुभयं भवति ।।

Nothing is higher than dharma. The weak overcomes the stronger by dharma, as over a king. Truly that dharma is the Truth (Satya); Therefore, when a man speaks the Truth, they say, "He speaks the Dharma"; and if he speaks Dharma, they say, "He speaks the Truth!" For both are one.

— Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4.xiv[49][50]

In the Epics[edit]

The Hindu religion and philosophy, claims Daniel Ingalls,[51] places major emphasis on individual practical morality. In the Sanskrit epics, this concern is omnipresent.

In the Second Book of Ramayana, for example, a peasant asks the King to do what dharma morally requires of him, the King agrees and does so even though his compliance with the law of dharma costs him dearly. Similarly, dharma is at the centre of all major events in the life of Rama, Sita, and Lakshman in Ramayana, claims Daniel Ingalls.[52] Each episode of Ramayana presents life situations and ethical questions in symbolic terms. The issue is debated by the characters, finally the right prevails over wrong, the good over evil. For this reason, in Hindu Epics, the good, morally upright, law-abiding king is referred to as "dharmaraja".[53]

In Mahabharata, the other major Indian epic, similarly, dharma is central, and it is presented with symbolism and metaphors. Near the end of the epic, the god Yama, referred to as dharma in the text, is portrayed as taking the form of a dog to test the compassion of Yudhishthira, who is told he may not enter paradise with such an animal, but refuses to abandon his companion, for which decision he is then praised by dharma.[54] The value and appeal of the Mahabharata is not as much in its complex and rushed presentation of metaphysics in the 12th book, claims Ingalls,[52] because Indian metaphysics is more eloquently presented in other Sanskrit scriptures; the appeal of Mahabharata, like Ramayana, is in its presentation of a series of moral problems and life situations, to which there are usually three answers given, according to Ingalls:[52] one answer is of Bhima, which is the answer of brute force, an individual angle representing materialism, egoism, and self; the second answer is of Yudhishthira, which is always an appeal to piety and gods, of social virtue and of tradition; the third answer is of introspective Arjuna, which falls between the two extremes, and who, claims Ingalls, symbolically reveals the finest moral qualities of man. The Epics of Hinduism are a symbolic treatise about life, virtues, customs, morals, ethics, law, and other aspects of dharma.[55] There is extensive discussion of dharma at the individual level in the Epics of Hinduism, observes Ingalls; for example, on free will versus destiny, when and why human beings believe in either, ultimately concluding that the strong and prosperous naturally uphold free will, while those facing grief or frustration naturally lean towards destiny.[56] The Epics of Hinduism illustrate various aspects of dharma, they are a means of communicating dharma with metaphors.[57]

According to 4th century Vatsyayana[edit]

According to Klaus Klostermaier, 4th century Hindu scholar Vātsyāyana explained dharma by contrasting it with adharma.[58] Vātsyāyana suggested that dharma is not merely in one's actions, but also in words one speaks or writes, and in thought. According to Vātsyāyana:[58][59]

Adharma of body: hinsa (violence), steya (steal, theft), pratisiddha maithuna (sexual indulgence with someone other than one's partner)

Dharma of body: dana (charity), paritrana (succor of the distressed) and paricarana (rendering service to others)

Adharma from words one speaks or writes: mithya (falsehood), parusa (caustic talk), sucana (calumny) and asambaddha (absurd talk)

Dharma from words one speaks or writes: satya (truth and facts), hitavacana (talking with good intention), priyavacana (gentle, kind talk), svadhyaya (self study)

Adharma of mind: paradroha (ill will to anyone), paradravyabhipsa (covetousness), nastikya (denial of the existence of morals and religiosity)

Dharma of mind: daya (compassion), asprha (disinterestedness), and sraddha (faith in others)

According to Patanjali Yoga[edit]

In the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali the dharma is real; in the Vedanta it is unreal.[60]

Dharma is part of yoga, suggests Patanjali; the elements of Hindu dharma are the attributes, qualities and aspects of yoga.[60] Patanjali explained dharma in two categories: yamas (restraints) and niyamas (observances).[58]

The five yamas, according to Patanjali, are: abstain from injury to all living creatures, abstain from falsehood (satya), abstain from unauthorised appropriation of things-of-value from another (acastrapurvaka), abstain from coveting or sexually cheating on your partner, and abstain from expecting or accepting gifts from others.[61] The five yama apply in action, speech and mind. In explaining yama, Patanjali clarifies that certain professions and situations may require qualification in conduct. For example, a fisherman must injure a fish, but he must attempt to do this with least trauma to fish and the fisherman must try to injure no other creature as he fishes.[62]

The five niyamas (observances) are cleanliness by eating pure food and removing impure thoughts (such as arrogance or jealousy or pride), contentment in one's means, meditation and silent reflection regardless of circumstances one faces, study and pursuit of historic knowledge, and devotion of all actions to the Supreme Teacher to achieve perfection of concentration.[63]

Sources[edit]

Dharma is an empirical and experiential inquiry for every man and woman, according to some texts of Hinduism.[40][64] For example, Apastamba Dharmasutra states:

Dharma and Adharma do not go around saying, "That is us." Neither do gods, nor gandharvas, nor ancestors declare what is Dharma and what is Adharma.

— Apastamba Dharmasutra[65]

In other texts, three sources and means to discover dharma in Hinduism are described. These, according to Paul Hacker, are:[66] First, learning historical knowledge such as Vedas, Upanishads, the Epics and other Sanskrit literature with the help of one's teacher. Second, observing the behaviour and example of good people. The third source applies when neither one's education nor example exemplary conduct is known. In this case, "atmatusti" is the source of dharma in Hinduism, that is the good person reflects and follows what satisfies his heart, his own inner feeling, what he feels driven to.[66]

Dharma, life stages and social stratification[edit]

Main articles: Āśrama and Puruṣārtha

Some texts of Hinduism outline dharma for society and at the individual level. Of these, the most cited one is Manusmriti, which describes the four Varnas, their rights and duties.[67] Most texts of Hinduism, however, discuss dharma with no mention of Varna (caste).[68] Other dharma texts and Smritis differ from Manusmriti on the nature and structure of Varnas.[67] Yet, other texts question the very existence of varna. Bhrigu, in the Epics, for example, presents the theory that dharma does not require any varnas.[69] In practice, medieval India is widely believed to be a socially stratified society, with each social strata inheriting a profession and being endogamous. Varna was not absolute in Hindu dharma; individuals had the right to renounce and leave their Varna, as well as their asramas of life, in search of moksa.[67][70] While neither Manusmriti nor succeeding Smritis of Hinduism ever use the word varnadharma (that is, the dharma of varnas), or varnasramadharma (that is, the dharma of varnas and asramas), the scholarly commentary on Manusmriti use these words, and thus associate dharma with varna system of India.[67][71] In 6th century India, even Buddhist kings called themselves "protectors of varnasramadharma" – that is, dharma of varna and asramas of life.[67][72]

At the individual level, some texts of Hinduism outline four āśramas, or stages of life as individual's dharma. These are:[73] (1) brahmacārya, the life of preparation as a student, (2) gṛhastha, the life of the householder with family and other social roles, (3) vānprastha or aranyaka, the life of the forest-dweller, transitioning from worldly occupations to reflection and renunciation, and (4) sannyāsa, the life of giving away all property, becoming a recluse and devotion to moksa, spiritual matters.

The four stages of life complete the four human strivings in life, according to Hinduism.[74] Dharma enables the individual to satisfy the striving for stability and order, a life that is lawful and harmonious, the striving to do the right thing, be good, be virtuous, earn religious merit, be helpful to others, interact successfully with society. The other three strivings are Artha – the striving for means of life such as food, shelter, power, security, material wealth, and so forth; Kama – the striving for sex, desire, pleasure, love, emotional fulfilment, and so forth; and Moksa – the striving for spiritual meaning, liberation from life-rebirth cycle, self-realisation in this life, and so forth. The four stages are neither independent nor exclusionary in Hindu dharma.[74]

Dharma and poverty[edit]

Dharma being necessary for individual and society, is dependent on poverty and prosperity in a society, according to Hindu dharma scriptures. For example, according to Adam Bowles,[75] Shatapatha Brahmana 11.1.6.24 links social prosperity and dharma through water. Waters come from rains, it claims; when rains are abundant there is prosperity on the earth, and this prosperity enables people to follow Dharma – moral and lawful life. In times of distress, of drought, of poverty, everything suffers including relations between human beings and the human ability to live according to dharma.[75]

In Rajadharmaparvan 91.34-8, the relationship between poverty and dharma reaches a full circle. A land with less moral and lawful life suffers distress, and as distress rises it causes more immoral and unlawful life, which further increases distress.[75][76] Those in power must follow the raja dharma (that is, dharma of rulers), because this enables the society and the individual to follow dharma and achieve prosperity.[77]

Dharma and law[edit]

Main article: Hindu law

The notion of dharma as duty or propriety is found in India's ancient legal and religious texts. Common examples of such use are Pitri Dharma (meaning a person's duty as a father), Putra Dharma (a person's duty as a son), Raj Dharma (a person's duty as a king) and so forth. In Hindu philosophy, justice, social harmony, and happiness requires that people live per dharma. The Dharmashastra is a record of these guidelines and rules.[78] The available evidence suggest India once had a large collection of dharma related literature (sutras, shastras); four of the sutras survive and these are now referred to as Dharmasutras.[79] Along with laws of Manu in Dharmasutras, exist parallel and different compendium of laws, such as the laws of Narada and other ancient scholars.[80][81] These different and conflicting law books are neither exclusive, nor do they supersede other sources of dharma in Hinduism. These Dharmasutras include instructions on education of the young, their rites of passage, customs, religious rites and rituals, marital rights and obligations, death and ancestral rites, laws and administration of justice, crimes, punishments, rules and types of evidence, duties of a king, as well as morality.[79]

Buddhism[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

| History[show] |

| Dharma Concepts [show] |

| Buddhist texts[show] |

| Practices[show] |

| Nirvāṇa[show] |

| Traditions[show] |

| Buddhism by country[show] |

| Outline |

| v t e |

Buddha's teachings[edit]

For practising Buddhists, references to "dharma" (dhamma in Pali) particularly as "the Dharma", generally means the teachings of the Buddha, commonly known throughout the East as Buddha-Dharma. It includes especially the discourses on the fundamental principles (such as the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Eightfold Path), as opposed to the parables and to the poems.

The status of Dharma is regarded variably by different Buddhist traditions. Some regard it as an ultimate truth, or as the fount of all things which lie beyond the "three realms" (Sanskrit: tridhatu) and the "wheel of becoming" (Sanskrit: bhavachakra), somewhat like the pagan Greek and Christian logos: this is known as Dharmakaya (Sanskrit). Others, who regard the Buddha as simply an enlightened human being, see the Dharma as the essence of the "84,000 different aspects of the teaching" (Tibetan: chos-sgo brgyad-khri bzhi strong) that the Buddha gave to various types of people, based upon their individual propensities and capabilities.

Dharma refers not only to the sayings of the Buddha, but also to the later traditions of interpretation and addition that the various schools of Buddhism have developed to help explain and to expand upon the Buddha's teachings. For others still, they see the Dharma as referring to the "truth", or the ultimate reality of "the way that things really are" (Tibetan: Chö).

The Dharma is one of the Three Jewels of Buddhism in which practitioners of Buddhism seek refuge, or that upon which one relies for his or her lasting happiness. The Three Jewels of Buddhism are the Buddha, meaning the mind's perfection of enlightenment, the Dharma, meaning the teachings and the methods of the Buddha, and the Sangha, meaning the monastic community who provide guidance and support to followers of the Buddha.

Chan Buddhism[edit]

Dharma is employed in Ch'an in a specific context in relation to transmission of authentic doctrine, understanding and bodhi; recognised in Dharma transmission.

Therevada Buddhism[edit]

In Theravada Buddhism obtaining ultimate realisation of the dhamma is achieved in three phases; learning, practising and realising.[82]

In Pali

pariyatti - the learning of the theory of dharma as contained within the suttas of the Pali canon

patipatti - putting the theory into practice and

pativedha - when one penetrates the dharma or through experience realises the truth of it.[82]

Jainism[edit]

Main article: Dharma (Jainism)

Jainism

The word Dharma in Jainism is found in all its key texts. It has a contextual meaning and refers to a number of ideas. In the broadest sense, it means the teachings of the Jinas,[10] or teachings of any competing spiritual school,[83] a supreme path,[84] socio-religious duty,[85] and that which is the highest mangala (holy).[86]

The major Jain text, Tattvartha Sutra mentions Das-dharma with the meaning of "ten righteous virtues". These are forbearance, modesty, straightforwardness, purity, truthfulness, self-restraint, austerity, renunciation, non-attachment, and celibacy.[87] Acārya Amṛtacandra, author of the Jain text, Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya writes:[88]

A right believer should constantly meditate on virtues of dharma, like supreme modesty, in order to protect the soul from all contrary dispositions. He should also cover up the shortcomings of others.

— Puruṣārthasiddhyupāya (27)

Dharmastikaay (Dravya)[edit]

The term dharmastikaay also has a specific ontological and soteriological meaning in Jainism, as a part of its theory of six dravya (substance or a reality). In the Jain tradition, existence consists of jiva (soul, atman) and ajiva (non-soul), the latter consisting of five categories: inert non-sentient atomic matter (pudgalastikaay), space (akasha), time (kala), principle of motion (dharmastikaay), and principle of rest (adharmastikaay).[89][90] The use of the term dharmastikaay to mean motion and to refer to an ontological sub-category is peculiar to Jainism, and not found in the metaphysics of Buddhism and various schools of Hinduism.[90]

Sikhism[edit]

Sikhism

Main article: Sikhism

For Sikhs, the word dharam (Punjabi: ਧਰਮ, romanized: dharam) means the path of righteousness and proper religious practice.[14] Guru Granth Sahib in hymn 1353 connotes dharma as duty.[91] The 3HO movement in Western culture, which has incorporated certain Sikh beliefs, defines Sikh Dharma broadly as all that constitutes religion, moral duty and way of life.[92]

Dharma in symbols[edit]

The wheel in the centre of India's flag symbolises Dharma.

The importance of dharma to Indian sentiments is illustrated by India's decision in 1947 to include the Ashoka Chakra, a depiction of the dharmachakra ( the "wheel of dharma"), as the central motif on its flag.[93]

See also[edit]

Dhammapada

Karma

List of Hindu empires and dynasties

Neo-Vedanta#Hindu inclusivism – Hindutva and Dharmic religions

Notes[edit]

^ Jump up to:a b c From the Oxford Dictionary of World Religions: "In Hinduism, dharma is a fundamental concept, referring to the order and custom which make life and a universe possible, and thus to the behaviours appropriate to the maintenance of that order."[10]

^ David Kalupahana: "The old Indian term dharma was retained by the Buddha to refer to phenomena or things. However, he was always careful to define this dharma as "dependently arisen phenomena" (paticca-samuppanna-dhamma) ... In order to distinguish this notion of dhamma from the Indian conception where the term dharmameant reality (atman), in an ontological sense, the Buddha utilised the conception of result or consequence or fruit (attha, Sk. artha) to bring out the pragmatic meaning of dhamma."[13]

^ Monier Williams, A Sanskrit Dictionary (1899): "to hold, bear (also bring forth), carry, maintain, preserve, keep, possess, have, use, employ, practise, undergo"[17]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

^ Gavin Flood (1994), Hinduism, in Jean Holm, John Bowker (Editors) – Rites of Passages, ISBN 1-85567-102-6, Chapter 3; Quote – "Rites of passage are dharma in action."; "Rites of passage, a category of rituals,..."

^ see:David Frawley (2009), Yoga and Ayurveda: Self-Healing and Self-Realization, ISBN 978-0-9149-5581-8; Quote – "Yoga is a dharmic approach to the spiritual life...";

Mark Harvey (1986), The Secular as Sacred?, Modern Asian Studies, 20(2), pp. 321–331.

^ see below:J. A. B. van Buitenen (1957), "Dharma and Moksa", Philosophy East and West, 7(1/2), pp. 33–40;

James Fitzgerald (2004), "Dharma and its Translation in the Mahābhārata", Journal of Indian philosophy, 32(5), pp. 671–685; Quote – "virtues enter the general topic of dharma as 'common, or general, dharma', ..."

^ Bernard S. Jackson (1975), "From dharma to law", The American Journal of Comparative Law, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Summer, 1975), pp. 490–512.

^ Harold Coward (2004), "Hindu bioethics for the twenty-first century", JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(22), pp. 2759–2760; Quote – "Hindu stages of life approach (ashrama dharma)..."

^ see:Austin Creel (1975), "The Reexamination of Dharma in Hindu Ethics", Philosophy East and West, 25(2), pp. 161–173; Quote – "Dharma pointed to duty, and specified duties..";

Gisela Trommsdorff (2012), Development of "agentic" regulation in cultural context: the role of self and world views, Child Development Perspectives, 6(1), pp. 19–26.; Quote – "Neglect of one's duties (dharma – sacred duties toward oneself, the family, the community, and humanity) is seen as an indicator of immaturity."

^ Wells, John C. (2008), Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.), Longman, ISBN 9781405881180

^ Jump up to:a b "Dharma". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-08-18.

^ Jump up to:a b See:Ludo Rocher (2003), The Dharmasastra, Chapter 4, in Gavin Flood(Editor), The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism, ISBN 978-0631215356.

Alban G. Widgery, "The Principles of Hindu Ethics", International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Jan. 1930), pp. 232–245.

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j "Dharma", The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions.

^ see:"Dharma", The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Ed. (2013), Columbia University Press, Gale, ISBN 978-0787650155;

Steven Rosen (2006), Essential Hinduism, Praeger, ISBN 0-275-99006-0, Chapter 3.

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f "dhamma", The New Concise Pali English Dictionary.

^ Jump up to:a b c David Kalupahana. The Philosophy of the Middle Way. SUNY Press, 1986, pp. 15–16.

^ Jump up to:a b Rinehart, Robin (2014), in Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech (Editors), The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies, ISBN 978-0199699308, Oxford University Press, pp. 138–139.

^ Jump up to:a b c d e see:English translated version by Jarrod Whitaker (2004): Horsch, Paul, "From Creation Myth to World Law: the Early History of Dharma", Journal of Indian Philosophy, December 2004, Volume 32, Issue 5–6, pp. 423–448; Original peer reviewed publication in German: Horsch, Paul, "Vom Schoepfungsmythos zum Weltgesetz", in Asiatische Studien: Zeitschrift der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Asiankunde, Volume 21 (Francke: 1967), pp. 31–61;

English translated version by Donald R. Davis (2006): Paul Hacker, "Dharma in Hinduism", Journal of Indian Philosophy", Volume 34, Issue 5, pp. 479–496; Original peer reviewed publication in German: Paul Hacker, "Dharma im Hinduismus" in Zeitschrift für Missionswissenschaft und Religionswissenschaft 49 (1965): pp. 93–106.

^ N. Velusamy and Moses Michael Faraday (Eds.) (2017). Why Should Thirukkural Be Declared the National Book of India? (in Tamil and English) (First ed.). Chennai: Unique Media Integrators. p. 55. ISBN 978-93-85471-70-4.

^ Monier Willams.

^ Day 1982, pp. 42–45.

^ Brereton, Joel P. (December 2004). "Dhárman In The Rgveda". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 32 (5–6): 449–489. doi:10.1007/s10781-004-8631-8. ISSN 0022-1791.

^ Rix, Helmut, ed. (2001). Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben (in German) (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. p. 145.

^ Karl Brugmann, Elements of the Comparative Grammar of the Indo-Germanic languages, Volume III, B. Westermann & Co., New York, 1892, p. 100.

^ "How did the 'Ramayana' and 'Mahabharata' come to be (and what has 'dharma' got to do with it)?".

^ Hiltebeitel, Alf (2011). Dharma: Its Early History in Law, Religion, and Narrative. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 36–37. ISBN 9780195394238.

^ Dhand, Arti (17 December 2002). "The Dharma of Ethics, the Ethics of Dharma: Quizzing the Ideals of Hinduism". Journal of Religious Ethics. 30 (3): 351. doi:10.1111/1467-9795.00113. ISSN 1467-9795.

^ J. A. B. Van Buitenen, "Dharma and Moksa", Philosophy East and West, Volume 7, Number 1/2 (April–July 1957), p. 36.

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Horsch, Paul, "From Creation Myth to World Law: the Early History of Dharma", Journal of Indian Philosophy, December 2004, Volume 32, Issue 5-6, pp. 423–448.

^ Hermann Grassmann, Worterbuch zum Rig-veda (German Edition), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120816367

^ Jump up to:a b c d e Steven Rosen (2006), Essential Hinduism, Praeger, ISBN 0-275-99006-0, pp. 34–45.

^ see:"Dharma" Monier Monier-Williams, Monier Williams Sanskrit-English Dictionary (2008 revision), pp. 543–544;

Carl Cappeller (1999), Monier-Williams: A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Etymological and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages, Asian Educational Services, ISBN 978-8120603691, pp. 510–512.

^ see:"...the order and custom which make life and a universe possible, and thus to the behaviours appropriate to the maintenance of that order". citation in The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions

Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, 2007.

^ see:Albrecht Wezler, "Dharma in the Veda and the Dharmaśāstras", Journal of Indian Philosophy, December 2004, Volume 32, Issue 5–6, pp. 629–654

Johannes Heesterman (1978). "Veda and Dharma", in W. D. O'Flaherty (Ed.), The Concept of Duty in South Asia, New Delhi: Vikas, ISBN 978-0728600324, pp. 80–95

K. L. Seshagiri Rao (1997), "Practitioners of Hindu Law: Ancient and Modern", Fordham Law Review, Volume 66, pp. 1185–1199.

^ seeअधर्मा "adharma", Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Germany (2011)

adharma Monier Williams Sanskrit Dictionary, University of Koeln, Germany (2009).

^ see:Gavin Flood (1998), "Making moral decisions", in Paul Bowen (Editor), Themes and issues in Hinduism, ISBN 978-0304338511, Chapter 2, pp. 30–54 and 151–152;

Coward, H. (2004), "Hindu bioethics for the twenty-first century", JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 291(22), pp. 2759–2760;

J. A. B. Van Buitenen, "Dharma and Moksa", Philosophy East and West, Volume 7, Number 1/2 (Apr. – Jul., 1957), p. 37.

^ RgVeda 6.70.1, 8.41.10, 10.44.8, for secondary source see Karl Friedrich Geldner, Der Rigveda in Auswahl (2 vols.), Stuttgart; and Harvard Oriental Series, 33–36, Bd. 1–3: 1951.

^ Paul Horsch, "From Creation Myth to World Law: the Early History of Dharma", Journal of Indian Philosophy, December 2004, Volume 32, Issue 5-6, pp. 430–431.

^ P. Thieme, Gedichte aus dem Rig-Veda, Reclam Universal-Bibliothek Nr. 8930, pp. 52.

^ Paul Horsch, "From Creation Myth to World Law: the Early History of Dharma", Journal of Indian Philosophy, December 2004, Volume 32, Issue 5-6, pp. 430–432.

^ Jump up to:a b Joel Brereton (2004), "Dharman in the RgVeda", Journal of Indian Philosophy, Vol. 32, pp. 449–489. "There are Indo-European parallels to dhárman (cf. Wennerberg 1981: 95f.), but the only Iranian equivalent is Old Persian darmān 'remedy', which has little bearing on Indo-Aryan dhárman. There is thus no evidence that IIr. *dharman was a significant culture word during the Indo-Iranian period." (p.449) "The origin of the concept of dharman rests in its formation. It is a Vedic, rather than an Indo-Iranian word, and a more recent coinage than many other key religious terms of the Vedic tradition. Its meaning derives directly from dhr 'support, uphold, give foundation to' and therefore 'foundation' is a reasonable gloss in most of its attestations." (p.485)

^ Morreall, John; Sonn, Tamara (2011). The Religion Toolkit: A Complete Guide to Religious Studies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 324. ISBN 9781444343717.

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Paul Hacker (1965), "Dharma in Hinduism", Journal of Indian Philosophy, Volume 34, Issue 5, pp. 479–496 (English translated version by Donald R. Davis (2006)).

^ Etienne Lamotte, Bibliotheque du Museon 43, Louvain, 1958, p. 249.

^ Barbara Holdrege (2004), "Dharma" in: Mittal & Thursby (Editors) The Hindu World, New York: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-21527-7, pp. 213–248.

^ Jump up to:a b Koller, J. M. (1972), "Dharma: an expression of universal order", Philosophy East and West, 22(2), pp. 136–142.

^ Māyā Monier-Williams Sanskrit English Dictionary, ISBN 978-8120603691

^ Northrop, F. S. C. (1949), "Naturalistic and cultural foundations for a more effective international law", Yale Law Journal, 59, pp. 1430–1441.

^ Day 1982, pp. 42–44.

^ "Dharma", The Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th Ed. (2013), Columbia University Press, Gale, ISBN 978-0787650155

^ Jump up to:a b J. A. B. Van Buitenen, "Dharma and Moksa", Philosophy East and West, Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (Apr. – Jul., 1957), pp. 33–40

^ Jump up to:a b Charles Johnston, The Mukhya Upanishads: Books of Hidden Wisdom, Kshetra, ISBN 978-1495946530, p. 481, for discussion: pp. 478–505.

^ Jump up to:a b Horsch, Paul (translated by Jarrod Whitaker), "From Creation Myth to World Law: The early history of Dharma", Journal of Indian Philosophy, Vol 32, pp. 423–448, (2004).

^ Daniel H. H. Ingalls, "Dharma and Moksa", Philosophy East and West, Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (Apr. – Jul., 1957), pp. 43.

^ Jump up to:a b c Daniel H. H. Ingalls, "Dharma and Moksa", Philosophy East and West, Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (April – July 1957), pp. 41–48.

^ The Mahābhārata: Book 11: The Book of the Women; Book 12: The Book of Peace, Part 1 By Johannes Adrianus Bernardus Buitenen, James L. Fitzgerald p. 124.

^ "The Mahabharata, Book 17: Mahaprasthanika Parva: Section 3".

^ There is considerable amount of literature on dharma-related discussion in Hindu Epics: of Egoism versus Altruism, Individualism versus Social Virtues and Tradition; for examples, see:Johann Jakob Meyer (1989), Sexual life in ancient India, ISBN 8120806387, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 92–93; Quote – "In Indian literature, especially in Mahabharata over and over again is heard the energetic cry – Each is alone. None belongs to anyone else, we are all but strangers to strangers; (...), none knows the other, the self belongs only to self. Man is born alone, alone he lives, alone he dies, alone he tastes the fruit of his deeds and his ways, it is only his work that bears him company. (...) Our body and spiritual organism is ever changing; what belongs, then, to us? (...) Thus, too, there is really no teacher or leader for anyone, each is his own Guru, and must go along the road to happiness alone. Only the self is the friend of man, only the self is the foe of man; from others nothing comes to him. Therefore what must be done is to honor, to assert one's self..."; Quote – "(in parts of the epic), the most thoroughgoing egoism and individualism is stressed..."

Raymond F. Piper (1954), "In Support of Altruism in Hinduism", Journal of Bible and Religion, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Jul., 1954), pp. 178–183

J Ganeri (2010), A Return to the Self: Indians and Greeks on Life as Art and Philosophical Therapy, Royal Institute of Philosophy supplement, 85(66), pp. 119–135.

^ Daniel H. H. Ingalls, "Dharma and Moksa", Philosophy East and West, Vol. 7, No. 1/2 (Apr. – Jul., 1957), pp. 44–45; Quote – "(...)In the Epic, free will has the upper hand. Only when a man's effort is frustrated or when he is overcome with grief does he become a predestinarian (believer in destiny)."; Quote – "This association of success with the doctrine of free will or human effort (purusakara) was felt so clearly that among the ways of bringing about a king's downfall is given the following simple advice: 'Belittle free will to him, and emphasise destiny.'" (Mahabharata 12.106.20).

^ Huston Smith, The World Religions, ISBN 978-0061660184, HarperOne (2009); For summary notes: Background to Hindu Literature Archived 2004-09-22 at the Wayback Machine

^ Jump up to:a b c Klaus Klostermaier, A survey of Hinduism, SUNY Press, ISBN 0-88706-807-3, Chapter 3: "Hindu dharma".

^ Jha, Nyayasutras with Vatsyayana Bhasya, 2 vols, Oriental Books (1939).

^ Jump up to:a b The yoga-system of Patanjali The ancient Hindu doctrine of concentration of mind, embracing the mnemonic rules, called Yoga-sutras, James Haughton Woods (1914), Harvard University Press[page needed]

^ The yoga-system of Patanjali Yoga-sutras, James Haughton Woods (1914), Harvard University Press, pp. 178–180.

^ The yoga-system of Patanjali Yoga-sutras, James Haughton Woods (1914), Harvard University Press, pp. 180–181.

^ The yoga-system of Patanjali Yoga-sutras, James Haughton Woods (1914), Harvard University Press, pp. 181–191.

^ Kumarila, Tantravarttika, Anandasramasamskrtagranthavalih, Vol. 97, pp. 204–205; For an English Translation, see Jha (1924), Bibliotheca Indica, Vol. 161, Vol. 1.

^ Olivelle, Patrick. Dharmasūtras: The Law Codes of Ancient India. Oxford World Classics, 1999.

^ Jump up to:a b Paul Hacker (1965), "Dharma in Hinduism", Journal of Indian Philosophy, Volume 34, Issue 5, pp. 487–489 (English translated version by Donald R. Davis (2006)).

^ Jump up to:a b c d e Alf Hiltebeitel (2011), Dharma: Its Early History in Law, Religion, and Narrative, ISBN 978-0195394238, Oxford University Press, pp. 215–227.

^ Thapar, R. (1995), The first millennium BC in northern India, Recent perspectives of early Indian history, 80–141.

^ Thomas R. Trautmann (1964), "On the Translation of the Term Varna", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, Vol. 7, No. 2 (Jul., 1964), pp. 196–201.

^ see:Van Buitenen, J. A. B. (1957). "Dharma and Moksa". Philosophy East and West, Volume 7, Number 1/2 (April – July 1957), pp. 38–39

Koller, J. M. (1972), "Dharma: an expression of universal order", Philosophy East and West, 22(2), pp. 131–144.

^ Kane, P.V. (1962), History of Dharmasastra (Ancient and Medieval Religious and Civil Law in India), Volume 1, pp. 2–10.

^ Olivelle, P. (1993). The Asrama System: The history and hermeneutics of a religious institution, New York: Oxford University Press.

^ Alban G. Widgery, "The Principles of Hindu Ethics", International Journal of Ethics, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Jan., 1930), pp. 232–245.

^ Jump up to:a b see:Koller, J. M. (1972), "Dharma: an expression of universal order", Philosophy East and West, 22(2), pp. 131–144.

Karl H. Potter (1958), "Dharma and Mokṣa from a Conversational Point of View", Philosophy East and West, Vol. 8, No. 1/2 (April – July 1958), pp. 49–63.

William F. Goodwin, "Ethics and Value in Indian Philosophy", Philosophy East and West, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Jan. 1955), pp. 321–344.

^ Jump up to:a b c Adam Bowles (2007), Dharma, Disorder, and the Political in Ancient India, Brill's Indological Library (Book 28), ISBN 978-9004158153, Chapter 3.

^ Derrett, J. D. M. (1959), "Bhu-bharana, bhu-palana, bhu-bhojana: an Indian conundrum", Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 22, pp. 108–123.

^ Jan Gonda, "Ancient Indian Kingship from the Religious Point of View", Numen, Vol. 3, Issue 1 (Jan., 1956), pp. 36–71.

^ Gächter, Othmar (1998). "Anthropos". Anthropos Institute.

^ Jump up to:a b Patrick Olivelle (1999), The Dharmasutras: The law codes of ancient India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-283882-2

^ Donald Davis, Jr., "A Realist View of Hindu Law", Ratio Juris. Vol. 19 No. 3 September 2006, pp. 287–313.

^ Lariviere, Richard W. (2003), The Naradasmrti, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass

^ Jump up to:a b What is the Triple Gem Dhamma: Good Dhamma is of three sorts. Ajaan Lee Dhammadharo (1994), p 33.

^ Cort, John E. (2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9.

^ Peter B. Clarke; Peter Beyer (2009). The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations. Taylor & Francis. p. 325. ISBN 978-1-135-21100-4.

^ Brekke, Torkel (2002). Makers of Modern Indian Religion in the Late Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-19-925236-7.

^ Cort, John E. (2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 192–194. ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9.

^ Jain 2011, p. 128.

^ Jain 2012, p. 22.

^ Cort, John E. (1998). Open Boundaries: Jain Communities and Cultures in Indian History. State University of New York Press. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-7914-3786-5.

^ Jump up to:a b Paul Dundas (2003). The Jains (2 ed.). Routledge. pp. 93–95. ISBN 978-0415266055.

^ W. Owen Cole (2014), in Pashaura Singh, Louis E. Fenech (Editors), The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies, ISBN 978-0199699308, Oxford University Press, pp. 254.

^ Verne Dusenbery (2014), in Pashaura Singh and Louis E. Fenech (Editors), The Oxford Handbook of Sikh Studies, ISBN 978-0199699308, Oxford University Press, pp. 560–568.

^ Narula, S. (2006), International Journal of Constitutional Law, 4(4), pp. 741–751.

Sources[edit]

Sanatana Dharma: an advanced text book of Hindu religion and Ethics. Central Hindu College, Benaras. 1904.

Day, Terence P. (1982), The Conception of Punishment in Early Indian Literature, Ontario: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, ISBN 978-0-919812-15-4

Murthy, K. Krishna. "Dharma – Its Etymology." The Tibet Journal, Vol. XXI, No. 1, Spring 1966, pp. 84–87.

Olivelle, Patrick (2009). Dharma: Studies in Its Semantic, Cultural and Religious History. Delhi: MLBD. ISBN 978-8120833388.

Jain, Vijay K. (2012), Acharya Amritchandra's Purushartha Siddhyupaya, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-4-5

Jain, Vijay K. (2011), Acharya Umasvami's Tattvārthsūtra, Vikalp Printers, ISBN 978-81-903639-2-1

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dharma |

Buddhism A-Z: "D" Entries

Rajiv Malhotra, Dharma Is Not The Same As Religion (huffingtonpost.com)

| Authority control | GND: 4135700-0 |

|---|

Categories: Buddhist philosophical concepts

Hindu philosophical concepts

Hindu law

Buddhist law

Puruṣārthas

Words and phrases with no direct English translation

Jain philosophical concepts

>>>

보리달마

위키백과, 우리 모두의 백과사전.

김명국의 달마도

보리달마(타밀어: போதிதர்மன் 보디다르마, 산스크리트어: बोधिधर्म, 중국어 정체자: 菩提達摩, 병음: Pútídámó, 생몰년 미상)는

인도 파사국 황실 남부 지방의 천축향지국 팔라바 왕가의 왕자로 출생하였으나,

왕족의 허울을 벗어던져버리고 북위 제국의 평범하기 짝없는 불제자로 귀화한 중국 북위의 불교 승려이다.[1]

그 설에 따르면, 중국 대륙에 선종을 포교한 남 인도지방 타밀 출신의 승려로,

고대 인도 불교의 제28 대 조사이자,

중국 선종의 제1 대 조사이며,

보통 달마(중국어 정체자: 達摩, 병음: Dámó)라고 줄여 부른다.

백육십 세까지 살았다는 전설이 있으나,

자세한 생몰년은 기록이 없다.

고기를 먹고 무예를 한 승려라는 전설도 있다.

목차

1전설에 나오는 생애

2역사상 사실

3같이 보기

4주해

5각주

6참고 자료

7외부 링크

전설에 나오는 생애[■편집]

천축향지국 왕의 셋째 아들로 남인도 파사국(타밀어: பல்லவர்)에서 태어났다.

470년 무렵 남중국에 와서 선종을 포교했다.

반야다라에게서 배우고 40년간 수도했다.

불심 깊던 양 무제와 선문답을 주고 받았다는 전설이 있다.[2]

520년 전후에 북위의 도읍 뤄양에 갔다가 그 후 허난 성 숭산 소림사에서 좌선수행(坐禪修行)에 정진하고,

그 선법(禪法)을 혜가 등에게 전수하였다.

달마의 전기에는 분명치 않은 점이 많다.

오늘날 우리가 익히 아는 염화미소나 보리달마를 다룬 여러 이야기는 후대에 꾸며진 전설로 신빙성이 전혀 없다.

염화미소 전설과 서역 28조의 전법설(傳法說)은 인도의 어떤 문헌에도 기록이 없고

중국 대륙 선종 초기 문헌에도 기록이 없다.

보리달마도 남북조시대에 서역에서 온 보리달마라는 이름의 중을 다룬 기록이 있지만,

그 사람은 낙양의 아름다운 불탑을 보고 경탄해마지 않는 매우 경건한 중이거나 불경인 『릉가경(楞伽經)』 중에서

무척 까다로운 경전에 통달하고 논리에 맞고 체계 있는 수련법이라고 주장하는

이입사행(二入四行)을 강조한 승려로서 선종 조사인 보리달마와는 그 성격이나 행적이 판이하다.

당송 시대 선종의 발전과 더불어 보리달마의 전기가 추가되고

여러 가지 허구를 이용한 전설이 보완되어 선종의 제1대 조사로서 달마상(達磨像)이 사실(史實)과 무관하게 허구로서 확립되었다.

양 무제와의 선문답을 다룬 이야기, 혜가가 눈 속에서 팔을 자르고 법을 전수받았다는 이야기,

서역에서 서방으로 돌아가는 보리달마를 만났다다는 이야기 등이 그것이다.

그가 좌선 수행 중에 졸음이 몰려와서 자신의 눈꺼풀을 떼어 던져버렸더니

그 자리에서 최초의 차 나무가 자라났다는 전설도 있다.[3]

그러나 보리달마는 『사권릉가경(四卷楞伽經)』을 중시하고 이입(二入)[4]·4행(四行)[5]을 교시하고,

북위 말기 귀족성을 띤 가람불교와 수행한 체험을 도외시한 강설불교(講說佛敎)를 날카로운 비판한 일,

중생의 동일진성(同一眞性)을 믿고 선을 실천하고 수행하는 노력 등은 사실로 인정된다.

제자에는 혜가·도육·승부·담림 등이 있다.

역사상 사실[■편집]

대한민국의 국적을 가진 사람들에게 널리 알려진, 달마를 다룬 여러 내용은 불교에서 지대하게 영향받아 중국에서 발흥한 종교인 선종이 중국에서 대단히 번성하자 종교상 권위의 원천인, 함부로 가까이할 수 없을 만큼 거룩하고 고결한 분위기와 심상을 연출하려고 후대에 꾸며진 이야기이므로 믿어서 근거나 증거로 삼을 수 있는 정도나 성질은 전혀 없다.

서역 이십팔조 傳法說이나 염화미소를 비롯한 전설은

인도의 어떤 문헌에서도 기록이 전무하고 중국 선종의 초기 문헌에서도 전혀 보이지 않듯이 달마도 마찬가지다.

보리달마라는 이름이 최초로 등장하는 문헌인, 5세기 東魏의 楊衒之가 쓴 『洛陽伽藍記』를 보면

남북조시대 때 서역에서 온 보리달마라는 이름의 승려를 다룬 기록이 있다.

"西域에서 온 보리달마라는 沙門이 있다. 페르시아 태생의 胡人이다.

멀리 변경 지역에서 중국에 막 도착하여 탑의 金盤이 햇빛을 받아 빛나고 光明이 구름을 뚫고 쏟아지며,

寶鐸이 바람에 울려 허공에 메아리치는 情景을 보면서 그자는 聖歌를 읊조려 찬탄하고 신의 조화가 분명하다고 칭송했다.

일백오십 세인 그자는 많은 나라를 돌아다녀 가보지 않은 곳이 없지만, 이토록 훌륭한 사찰은 이 지상에서 존재하지 않고 佛國을 찾아도 이만한 곳은 아닐 듯하다고 말한 뒤 '南無南無'(namunamu ; 歸依)를 부르면서 며칠이나 계속하여 合掌했다."[6]

하지만, 이 기록 내용에서의 보리달마는 洛陽의 아름다운 불탑을 보고 敬歎해마지 않는 매우 敬虔한 승려이거나 불경인 『楞伽經』 중에 매끄럽지 못하면서 어렵고 무척 까다로운 四卷本『楞伽經』에 통달하고 二入四行[주 1]이라는, 논리에 부합하고 체계 있는 수련법을 강조한 승려로서 선종의 보리달마와는 그 성격이나 행적이 아주 다르다.

근 90%가 11세기 이후에 작성되거나 인쇄된 방대한 둔황문헌[주 2] 중에 보이는 몇몇 기록에서의 보리달마도 인도 불교에 지대히 영향받아 중국에서 발흥한 종교인 선종에서 추존하는 보리달마와는 사상과 수행하는 방법과 이론·논리 구조가 전혀 다르다.

보리달마가 소림사 일대인 허난성 송루어에 머문 문헌상 시점은 북위 시대 초 孝文帝 즉위 10년인 486년에서 孝文帝 즉위 19년인 495년이지만 당시 허난성 송루어에는 소림사라는 사찰은 있지도 않았으므로[7] 보리달마는 소림사와는 아무런 관계가 없듯이 보리달마를 다룬 이야기는 후대 선종이 득세하면서 보리달마를, 선종을 상징하는 인재로 追尊하고자 꾸며낸 여러 가지 전설 중의 하나에 불과하다.

같이 보기[■편집]

석가모니

파사국

소림사

선종

주해[■편집]

↑ 二入四行은 득도하는 근본이 되는 방법을 理入과 行入으로 양분하고 行入을 四分한 수행법 일종으로서 그 내용은 一、 理入: 불경에 의거하여 불타의 근본이 되는 의미를 깨달음。 二、行入: 불타의 근본 뜻을 깨달으려는 수행으로서 이 行入을 四行으로 四分(一、報怨行: 수행하는 사람이 고통당할 때는 過報라고 판단해 다른 사람을 못마땅하게 여기어 탓하거나 불평하면서 미워하지 않는 방법。 一、隨緣行: 인연 따라 일어나고 사라져 없어지는 苦樂에 알맞은 상태로 변하는 방법. 一、無所求行: 밖에서 구하고 대상에 마음이 늘 쏠려 잊지 못하여 매달리지 말고 空을 깨달아 자신이 좋아하는 대상을 갖고 싶거나 구하고 싶은 마음과 대상에 마음이 늘 기울어져 잊지 못하고 매달리는 마음을 버리는 방법。 一、稱法行: 자신의 품격과 성질은 본디 맑고 깨끗하다는 空이 처한 형편에서 空을 실행하기에 꼭 알맞은 布施와 忍辱과 持戒와 精進과 禪定과 智慧를 연수하는 방법)。

↑ 敦煌文獻. 莫高窟을 위시한 둔황 일원 석굴 유적에서 발견된 고대 한문 · 산스크리트어 · 위구르어 · 소그드어 · 구자어 · 호탄어 · 티베트어 · 몽골어, 히브리어로 쓰인 문헌 대부분은 사본이지만, 『金剛經』처럼 일부는 인쇄본도 있기에 『둔황사본』이라는 통칭은 부당하고 문서는 다분히 사료나 서적과 구별되는 서류라는 뜻으로 사용되므로 둔황 석굴 유적에서 나온 典籍 다량은 포괄할 수가 없어 이것도 지양해야 해서 문서나 사본 전반을 갈무리해 학술 연구에서 典據나 참고가 될 만한 자료인, 3%에서 4%만이 연대가 표기된 둔황문헌은 4세기 후반에서 11세기 전반으로 추정되는 중 80%에서 90%는 9세기 이후에 작성됐다. 둔황문헌 내용은 다종다양하지만, 불교 문헌이 압도해서 거의 90%를 차지한다. 한문과 티베트 문자로 쓰인 불교 문헌에서도 불경 사본이 가장 많다. 『金剛般若波羅密經』 사본이 1000여 점에 달하듯이 같은 경전이 숱하게 중복된다. 불경 다음으로는 도교 문헌이 많고 유교 문헌도 1% 이상 있다. 史籍으로는 『史記』, 『漢書』 『文選』, 『甘棠集』, 『往五天竺國傳』을 위시해 다수한 필사본 殘簡이 끼어 있다. 둔황문헌에서는 문서가 각별히 주목을 끈다. 고문서 전통이 거의 없는 중국으로서는 소중히 간수해야 할 문헌이다. 사원 승려 명부, 재산 등록부, 收支 장부, 戒牒[징계장] 등 사원 관련 문서가 1000여 점이나 되어 당시 불교 사원의 일상을 엿볼 수 있다. 일반 주민과 관련된 문서로는 호적, 役務 臺帳, 물자 징수 장부, 매매ㆍ대여, 고용상 계약서, 가산 분할이나 양자와 이혼, 노예해방 같은 일상에 관한 證書가 있다. ※출처: 정수일 선생, 『실크로드 사전』, 창비, 2013. 10.31.

각주[■편집]

↑ 양현지(楊衒之), 《낙양가람기(洛陽伽藍記)》, 547년.

↑ 《글로벌 세계대백과사전》

↑ 조은아 (2012). 《중국차 이야기》. 살림출판사. 8쪽. ISBN 9788952219374.

↑ 이입과 행입(行入)

↑ 보행(報行)·수록행(隨綠行)·무소구행(無所求行)·칭법행(稱法行)

↑ 5세기경 東魏 楊衒之가 편찬한 『洛陽伽藍記』.

↑ 『魏書』 제114 권 「釋老志」

참고 자료[■편집]

외부 링크[■편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다.보리달마 |

| 제1대 중국 선종의 조사 457년 ~ 528년 | 후임 혜가 |

| 접기v t e | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 주요 종지 |

|  | |||||||

| 여래・보살 | 석가여래 등 | ||||||||

| 사상・교리 | 간화선 묵조선 염화미소 정법안장 열반묘심 실상무상 미묘법문 불립문자 교외별전 | ||||||||

| 경전・어록 | 이입사행론 육조단경 임제록 무문관 벽암록 종용록 선문염송 전등록 | ||||||||

| 관련인물 |

| ||||||||

>>>>

Bodhidharma

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Bodhidharma

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

Bodhidharma, Ukiyo-e woodblock print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1887. Bodhidharma, Ukiyo-e woodblock print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1887. | |||

| Title | Chanshi 1st Chan Patriarch | ||

| Personal | |||

| Religion | Buddhism | ||

| School | Chan | ||

| Senior posting | |||

| Successor | Huike | ||

| Students[show] | |||

| Part of a series on |

| Zen Buddhism |

|---|

|

| Main articles[show] |

| Persons[show] |

| Doctrines[show] |

| Traditions[show] |

| Awakening[show] |

| Teachings[show] |

| Practice[show] |

| Schools[show] |

| Related schools[show] |

| v t e |

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese Buddhism 汉传佛教 / 漢傳佛教 |

|---|

|

| History[show] |

| Major figures[show] |

| Traditions[show] |

| Texts[show] |

| Architecture[show] |

| Bodhimaṇḍas[show] |

| Culture[show] |

| v t e |

Little contemporary biographical information on Bodhidharma is extant, and subsequent accounts became layered with legend and unreliable details.[2][note 1]

According to the principal Chinese sources, Bodhidharma came from the Western Regions,[5][6] which refers to Central Asia but may also include the Indian subcontinent, and was either a "Persian Central Asian"[5] or a "South Indian [...] the third son of a great Indian king."[6][note 2] Throughout Buddhist art, Bodhidharma is depicted as an ill-tempered, profusely-bearded, wide-eyed non-Chinese person. He is referred as "The Blue-Eyed Barbarian" (Chinese: 碧眼胡; pinyin: Bìyǎnhú) in Chan texts.[11]

Aside from the Chinese accounts, several popular traditions also exist regarding Bodhidharma's origins.[note 4]

The accounts also differ on the date of his arrival, with one early account claiming that he arrived during the Liu Song dynasty (420–479) and later accounts dating his arrival to the Liang dynasty (502–557). Bodhidharma was primarily active in the territory of the Northern Wei (386–534). Modern scholarship dates him to about the early 5th century.[16]

Bodhidharma's teachings and practice centered on meditation and the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. The Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (952) identifies Bodhidharma as the 28th Patriarch of Buddhism in an uninterrupted line that extends all the way back to the Gautama Buddha himself.[17] Bodhidharma also known as " The Wall Gazing Brahmin " .[18]

Contents

1Biography1.1Principal sources1.1.1The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang

1.1.2Tánlín – preface to the Two Entrances and Four Acts

1.1.3"Chronicle of the Laṅkāvatāra Masters"

1.1.4"Further Biographies of Eminent Monks"

1.2Later accounts1.2.1Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall

1.2.2Record of the Masters and Students of the Laṅka

1.2.3Dàoyuán – Transmission of the Lamp

1.3Popular traditions

2Legends about Bodhidharma2.1Encounter with Emperor Xiāo Yǎn 蕭衍

2.2Nine years of wall-gazing

2.3Huike cuts off his arm

2.4Transmission2.4.1Skin, flesh, bone, marrow

2.5Bodhidharma at Shaolin

2.6Travels in Southeast Asia

2.7Appearance after his death

3Practice and teaching3.1Pointing directly to one's mind

3.2Wall-gazing

3.3The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

4Lineage4.1Construction of lineages

4.2Six patriarchs

4.3Continuous lineage from Gautama Buddha

5Modern scholarship5.1Biography as a hagiographic process

5.2Origins and place of birth

5.3Caste

5.4Name

5.5Abode in China

5.6Shaolin boxing

6Works attributed to Bodhidharma

7See also

8Notes

9References

10Sources10.1Printed sources

10.2Web sources

10.3Further reading

11External links

Biography

Principal sources

.png/220px-Western_Regions_1st_century_BC(en).png)

The Western Regions in the first century BCE.

There are two known extant accounts written by contemporaries of Bodhidharma. According to these sources, Bodhidharma came from the Western Regions,[5][6] and was either a "Persian Central Asian"[5] or a "South Indian [...] the third son of a great Indian king."[6] Later sources draw on these two sources, adding additional details, including a change to being descendent from a Brahmin king,[8][9] which accords with the reign of the Pallavas, who "claim[ed] to belong to a brahmin lineage."[web 2][19]

The Western Regions was a historical name specified in the Chinese chronicles between the 3rd century BC to the 8th century AD[20] that referred to the regions west of Yumen Pass, most often Central Asia or sometimes more specifically the easternmost portion of it (e.g. Altishahr or the Tarim Basin in southern Xinjiang). Sometimes it was used more generally to refer to other regions to the west of China as well, such as the Indian subcontinent (as in the novel Journey to the West).

The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang

Blue-eyed Central Asian monk teaching an East Asian monk. A fresco from the Bezeklik, dated to the 9th or 10th century; although Albert von Le Coq (1913) assumed the red-haired monk was a Tocharian,[21] modern scholarship has identified similar Caucasian figures of the same cave temple (No. 9) as ethnic Sogdians,[22] an Eastern Iranian people who inhabited Turfan as an ethnic minority community during the phases of Tang Chinese (7th–8th century) and Uyghur rule (9th–13th century).[23]

The earliest text mentioning Bodhidharma is The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang (Chinese: 洛陽伽藍記 Luòyáng Qiélánjì) which was compiled in 547 by Yáng Xuànzhī (楊衒之), a writer and translator of Mahayana sutras into Chinese. Yang gave the following account:

At that time there was a monk of the Western Region named Bodhidharma, a Persian Central Asian.[note 5] He traveled from the wild borderlands to China. Seeing the golden disks on the pole on top of Yǒngníng's stupa reflecting in the sun, the rays of light illuminating the surface of the clouds, the jewel-bells on the stupa blowing in the wind, the echoes reverberating beyond the heavens, he sang its praises. He exclaimed: "Truly this is the work of spirits." He said: "I am 150 years old, and I have passed through numerous countries. There is virtually no country I have not visited. Even the distant Buddha-realms lack this." He chanted homage and placed his palms together in salutation for days on end.[5]

The account of Bodhidharma in the Luoyan Record does not particularly associate him with meditation, but rather depicts him as a thaumaturge capable of mystical feats. This may have played a role in his subsequent association with the martial arts and esoteric knowledge.[24]

Tánlín – preface to the Two Entrances and Four Acts

A Dehua ware porcelain statuette of Bodhidharma from the late Ming dynasty, 17th century

The second account was written by Tánlín (曇林; 506–574). Tánlín's brief biography of the "Dharma Master" is found in his preface to the Long Scroll of the Treatise on the Two Entrances and Four Practices, a text traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma and the first text to identify him as South Indian:

The Dharma Master was a South Indian of the Western Region. He was the third son of a great Indian king. His ambition lay in the Mahayana path, and so he put aside his white layman's robe for the black robe of a monk […] Lamenting the decline of the true teaching in the outlands, he subsequently crossed distant mountains and seas, traveling about propagating the teaching in Han and Wei.[6]

Tánlín's account was the first to mention that Bodhidharma attracted disciples,[25] specifically mentioning Dàoyù (道育) and Dazu Huike (慧可), the latter of whom would later figure very prominently in the Bodhidharma literature. Although Tánlín has traditionally been considered a disciple of Bodhidharma, it is more likely that he was a student of Huìkě.[26]

"Chronicle of the Laṅkāvatāra Masters"

Tanlin's preface has also been preserved in Jingjue's (683–750) Lengjie Shizi ji "Chronicle of the Laṅkāvatāra Masters", which dates from 713–716.[4]/ca. 715[7] He writes,

The teacher of the Dharma, who came from South India in the Western Regions, the third son of a great Brahman king."[8]

"Further Biographies of Eminent Monks"

This Japanese scroll calligraphy of Bodhidharma reads, "Zen points directly to the human heart, see into your nature and become Buddha." It was created by Hakuin Ekaku

In the 7th-century historical work "Further Biographies of Eminent Monks" (續高僧傳 Xù gāosēng zhuàn), Daoxuan (道宣) possibly drew on Tanlin's preface as a basic source, but made several significant additions:

Firstly, Daoxuan adds more detail concerning Bodhidharma's origins, writing that he was of "South Indian Brahman stock" (南天竺婆羅門種 nán tiānzhú póluómén zhŏng).[9]

Secondly, more detail is provided concerning Bodhidharma's journeys. Tanlin's original is imprecise about Bodhidharma's travels, saying only that he "crossed distant mountains and seas" before arriving in Wei. Daoxuan's account, however, implies "a specific itinerary":[27] "He first arrived at Nan-yüeh during the Sung period. From there he turned north and came to the Kingdom of Wei"[9] This implies that Bodhidharma had travelled to China by sea and that he had crossed over the Yangtze.

Thirdly, Daoxuan suggests a date for Bodhidharma's arrival in China. He writes that Bodhidharma makes landfall in the time of the Song, thus making his arrival no later than the time of the Song's fall to the Southern Qi in 479.[27]

Finally, Daoxuan provides information concerning Bodhidharma's death. Bodhidharma, he writes, died at the banks of the Luo River, where he was interred by his disciple Dazu Huike, possibly in a cave. According to Daoxuan's chronology, Bodhidharma's death must have occurred prior to 534, the date of the Northern Wei's fall, because Dazu Huike subsequently leaves Luoyang for Ye. Furthermore, citing the shore of the Luo River as the place of death might possibly suggest that Bodhidharma died in the mass executions at Heyin (河陰) in 528. Supporting this possibility is a report in the Chinese Buddhist canon stating that a Buddhist monk was among the victims at Héyīn.[28]

Later accounts

Bodhidharma, stone carving in Shaolin Temple.

Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall

In the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (祖堂集 Zǔtángjí) of 952, the elements of the traditional Bodhidharma story are in place. Bodhidharma is said to have been a disciple of Prajñātāra,[29] thus establishing the latter as the 27th patriarch in India. After a three-year journey, Bodhidharma reached China in 527,[29] during the Liang (as opposed to the Song in Daoxuan's text). The Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall includes Bodhidharma's encounter with Emperor Wu of Liang, which was first recorded around 758 in the appendix to a text by Shenhui (神會), a disciple of Huineng.[30]

Finally, as opposed to Daoxuan's figure of "over 180 years,"[4] the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall states that Bodhidharma died at the age of 150. He was then buried on Mount Xiong'er (熊耳山 Xióng'ĕr Shān) to the west of Luoyang. However, three years after the burial, in the Pamir Mountains, Sòngyún (宋雲)—an official of one of the later Wei kingdoms—encountered Bodhidharma, who claimed to be returning to India and was carrying a single sandal. Bodhidharma predicted the death of Songyun's ruler, a prediction which was borne out upon the latter's return. Bodhidharma's tomb was then opened, and only a single sandal was found inside.

According to the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall, Bodhidharma left the Liang court in 527 and relocated to Mount Song near Luoyang and the Shaolin Monastery, where he "faced a wall for nine years, not speaking for the entire time",[31] his date of death can have been no earlier than 536. Moreover, his encounter with the Wei official indicates a date of death no later than 554, three years before the fall of the Western Wei.

Record of the Masters and Students of the Laṅka

The Record of the Masters and Students of the Laṅka, which survives both in Chinese and in Tibetan translation (although the surviving Tibetan translation is apparently of older provenance than the surviving Chinese version), states that Bodhidharma is not the first ancestor of Zen, but instead the second. This text instead claims that Guṇabhadra, the translator of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, is the first ancestor in the lineage. It further states that Bodhidharma was his student. The Tibetan translation is estimated to have been made in the late eighth or early ninth century, indicating that the original Chinese text was written at some point before that.[32]

Dàoyuán – Transmission of the Lamp