| 일 | 월 | 화 | 수 | 목 | 금 | 토 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 |

| 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 |

| 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

- 수능엄경

- 종경록

- 대방광불화엄경60권본

- 마하반야바라밀경

- Japan

- 무량의경

- 유마경

- 대반열반경

- 아미타불

- 유마힐소설경

- 유가사지론

- 원각경

- 금강삼매경론

- 반야심경

- 정법화경

- 마하승기율

- 대지도론

- 대반야바라밀다경

- 잡아함경

- 마명

- 가섭결경

- 중아함경

- 방광반야경

- 장아함경

- 대승기신론

- 증일아함경

- 대방광불화엄경

- 백유경

- 근본설일체유부비나야

- 묘법연화경

- Since

- 2551.04.04 00:39

- ™The Realization of The Good & The Right In Wisdom & Nirvāṇa Happiness, 善現智福

- ॐ मणि पद्मे हूँ

불교진리와실천

호마_위키백과스크랩 본문

>>>

불기2564-12-31 호마 관련 위키백과 스크랩

https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/호마_(의식)

호마 (의식)

위키백과, 우리 모두의 백과사전.![]() 이 문서는 밀교의 호마 의식에 관한 것입니다. 힌두교의 호마 의식에 대해서는 야즈나 문서를 참조하십시오.

이 문서는 밀교의 호마 의식에 관한 것입니다. 힌두교의 호마 의식에 대해서는 야즈나 문서를 참조하십시오.

| 불교 |

|---|

|

| 교의와 용어[보이기] |

| 인물[보이기] |

| 역사와 종파[보이기] |

| 경전[보이기] |

| 성지[보이기] |

| 지역별 불교[보이기] |

| v t e |

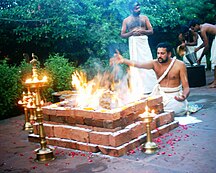

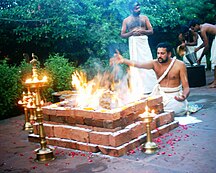

지혜의 불로 미혹·번뇌의 나무를 태우고,

진리의 성화(性火)로 마해(魔害)를 없애는 것을 뜻하는 밀교의 수법(修法)이다.

이것은 본래 인도에서 화신(火神) 아그니(Agni)를 공양(供養)해서 악마를 제거하고

행복을 얻기 위해 행하여진 화제(火祭)를 불교에 채용한 것으로 되어 있다.

밀교의 수행법으로서는

본존·

노(爐)·

행자(行者)의 3위(三位)가 구족(具足)해야 하며,

부동명왕(不動明王)이나 애염명왕(愛染明王) 등을 본존으로 하고

그 앞에 의칙(儀則)에 의거한 화로(火爐)가 있는 호마단(護摩壇)을 놓고,

행자(行者)가 규정된 호마목(護摩木)을 태워

불 속에 곡물 등을 던져 공양하며,

재난을 제거하고 행복을 가져올 것을 기원한다.

이처럼 실제로 호마단을 향하여 올리는 유형적(流刑的)인 의식 수법을

외호마(外護摩)·사호마(事護摩)라 하고,

이에 대하여 화단(火壇)을 향하지 않고

자신을 단장(壇場)으로 하여

불(佛)의 지화(智火)로

내심의 번뇌(煩惱)나 업을 태우는 것을 내호마(內護摩)·이호마(理護摩)라 한다.

또한 이 수법(修法)의 기원의 취지를

나무판자나 종이에 쓴 것을 호마찰(護摩札)이라 하여 호부(護符)로 쓴다.

각주[■편집]

↑ Timothy Lubin (2015). Michael Witzel, 편집. 《Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée》. Oxford University Press. 143–166쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel, 편집. 《Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée》. Oxford University Press. 1–3쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ Axel Michaels (2016). 《Homo Ritualis: Hindu Ritual and Its Significance for Ritual Theory》. Oxford University Press. 237–248쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

외부 링크[■편집]

| 위키미디어 공용에 관련된 미디어 분류가 있습니다.호마 |

Agnihotra Firehoma

Association for Homa-Therapy agnihotra-online.com

Tantric Fire

| 펼치기v t e |

|---|

| 전거 통제 | NDL: 00562540 |

|---|

분류: 밀교 (불교)

종교 의식

수험도

○ 2020_0911_110959_nik_ori_rs 제천 의림지 대도사

○ 2020_0909_132754_can_CT27 무주 백련사

○ 2020_0904_130700_can_bw24 원주 구룡사

○ 2019_1105_132510_nik_ct2_s12 순천 조계산 선암사

○ 2020_1114_131845_can_Ar37_s12 삼각산 도선사

○ 2020_0908_170636_nik_Ab31 합천 해인사 백련암

○ 2019_1201_164415_nik_ab15_s12 원주 구룡사

○ 2020_1114_144252_can_ar13 삼각산 도선사

○ 2020_0908_152704_nik_ar47 합천 해인사

○ 2020_0909_122626_can_CT33 무주 백련사

○ 2020_0905_162927_can_ar26 오대산 적멸보궁

○ 2019_1201_161536_nik_ab39_s12 원주 구룡사

○ 2019_1106_103801_nik_Ar28 화순 영구산 운주사

○ 2018_1024_163837_nik_ori 부여 고란사

○ 2019_1105_155517_can_CT27 순천 조계산 송광사

○ 2020_0906_123107_can_BW17 천축산 불영사

○ 2019_1105_111913_nik_Ab27 순천 조계산 선암사

○ 2019_1106_121408_can_AB7 화순 영구산 운주사

○ 2019_1104_104753_can_ct30_s12 구례 화엄사

○ 2020_0909_155249_can_ar45 무주 백련사

○ 2020_0910_181911_nik_BW25 월악산 신륵사

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/護摩

>>>

호마

위키 백과 사전 「위키 페디아 (Wikipedia)」

일어번역 by 구글 [ 오류는 원문 참조 ]

童学寺의 호마

효고현 미키시 의 가야 원 에서 수도자 따라 매년 10 월 둘째 월요일에 열리는 채용燈大호마 공급

힌두교의 호마

호마 (참깨, 자격증 : homa , 호마)는 인도 계 종교 에서 행해지는 불 을 사용하는 의식 .

"제물" "제물을 바치기」 「희생」 「제사」를 의미하는 산스크리트어 의 호마 ( homa )를 음역하여 베껴 쓴 단어이다 [1] .

목차

1바라문교 · 조로아스터 교

2불교2.1호마의 종류

2.2야외 호마 법회

3신도

4각주

5관련 항목

바라문교 · 조로아스터 교 [ 편집 ]

인도 에서 기원전 1000 년 무렵부터 성립 된 베다 경전 에 나와있는 바라문교 의 종교 의례이다. 더 거슬러 올라가면 인도 ·이란 공통 시대의 아리아 종교 의례로서, 화염 숭배 에 기원을 가진다. 그러므로 경배 불 교 라고도한다 조로아스터 교 도 공통同根의 문화이다.

불교 [ 편집 ]

불교 는 석가모니 입멸 에서 약 500 년 후에 발생한 대승 불교 의 중기부터 후기 ( 밀교 )의 과정에서 힌두교 ( 바라문교 )에서 받아 들여진 것이라고 생각되고있다. 따라서 호마는 밀교 (대승 불교의 일파)에만 존재하는修法이다. 따라서 기본적으로는 일본 의 천태종 · 진언종 과 티베트 불교 등 밀교 계통의 종파에서만 이루어진다. 또한, 독점적으로 호마를修する위한 당의 처마 를 "護摩堂"(護摩堂)라고 칭한다.

호마의 종류 [ 편집 ]

護摩壇에 불을 점자 불 속에 제물을 들여 이어 호마 나무 를 들여 기원하는 외부 호마 와

자신을 제단에 비유 부처님의 지혜의 불에 자신의 마음 속에있는 번뇌 와 업 에 불을 붙여 태워 버릴 안에 호마 가있다.

또한, 개별 목적에 따라 일반적으로 다음의 다섯 가지로 분류된다.

장수 법 (소쿠 바느질) ... 재해없는 것을기도하며, 가뭄, 강풍, 홍수, 지진, 화재를 비롯해 개인적인 고난, 번뇌도 대상.

증익 법 (그렇지やくほう) ...

단순히 재해를 제외뿐만 아니라 적극적으로 행복을 두 배로. 복덕 번영을 목적으로하는修法. 장수 연명, 결연 도 그 대상.

調伏법 (ちょうぶく편) ...怨敵,魔障을 제거하는修法. 악행을 억제 할 목적이기 때문에, 다른修法보다 뛰어난阿闍梨이 이렇게.

경애 법 (경애 편) ... 調伏과는 반대로 다른 사람을 존중하고 사랑하는 평화 원만을 기원하는 법.

鉤召 법 (이렇게 첩보) ... 여러 존 · 선신 · 사랑하는 사람을 불러 모으는위한 修法.

야외 호마 법회 [ 편집 ]

슈 겐도 에서 야외에서 수정되는 전통적인 호마 법회를柴燈·採燈(등불) (사이토) 호마한다.

일본의 전통적인 양대 슈 겐도 유파 인 진언 계当山파에서는 산중에서 정식 조밀 장비의 장엄도 잘 못하고,

시바 장작에서 단군을 마련하기 위해 「시바 등 "이라 함

한편, 같은 전통 유파에서 있는 천태종 계 본산 파에서는 진언 계当山파의 시바 등에서 채화하고 호마를修する있게 되었기 때문에 ' 채택 등 "이라 칭한다.

최근에는 전통적인 본산 파 ·当山파의 유파에 속하지 않는 사찰, 또한 분파 독립적 인宗団과 밀교 계통 신종교 등에서도 자신의 방식으로 해석하여 "제나라燈護타마」(真如苑真澄寺)와 '大柴燈護摩供"(阿含宗)"저희 불 피워」 「불 축제 "등의 별칭을 사용하여 실시되고있다.

신도 [ 편집 ]

호마는 본래는 불교의 밀교修法이기 때문에, 밀교와 슈 겐도에서 행해지지만, 신도 의 신사 의 일부라도 호마가 실시된다. 원래 신불 습합 이었다 권현 사나 궁이 메이지 유신 의 신불 분리 (신불 판연令)에 의해 사원을 다른 법인으로 개편 한 사례도 적지 않지만 현재에도 신사에서 신관 과 수도자 에 의한 호마 축제가 계속되고있다 수있다.

아타고 신사 ( 교토 부 교토시 )의 천일 참배의 저녁 어饌祭[2]

야스이 금 비라 궁 ( 교토 부 교토시 ) 춘계 금 비라 대제 추계 화재焚祭[3]

쿠마 노 나치 타이 샤 ( 와카야마 현 히가시 무로 군 나 치카 쓰 우라 정 )의 권현 강 축제 [4]

八菅신사 ( 가나가와 현 아이카와 정 )의 예대의 호마 공양 불 생 삼매의修法[5]

각주 [ 편집 ]

^ 진언종 지산 파 대본 산川崎大師금강산平間寺| 효험 | 저희 호마

^ 아타고 신사 | 천일 참배

^ 야스이 금 비라 궁 | 연중 행사

^ 쿠마 노 나치 타이 샤 | 권현 강 축제 안내

^ NPO 법인 시니어 넷 사가 미하라 | 사가 미하라 백선 | 사가 미하라의 사찰 문화재 |八菅신사

관련 항목 [ 편집 ]

화염 숭배

카지 · 기도

大柴 燈護 摩供

| |||

>>>

護摩

出典: フリー百科事典『ウィキペディア(Wikipedia)』

童学寺の護摩

兵庫県三木市の伽耶院で山伏により毎年10月第2月曜日に行われる採燈大護摩供

ヒンドゥー教におけるホーマ

護摩(ごま、梵: homa, ホーマ)とは、インド系宗教において行われる火を用いる儀式。「供物」「供物をささげること」「犠牲」「いけにえ」を意味するサンスクリットのホーマ(homa)を音訳して書き写した語である[1]。

目次

1バラモン教・ゾロアスター教

2仏教2.1護摩の種類

2.2野外の護摩法要

3神道

4脚注

5関連項目

バラモン教・ゾロアスター教[編集]

インドで紀元前1000年頃から成立したヴェーダ聖典に出ているバラモン教の宗教儀礼である。さらに遡れば、インド・イラン共通時代のアーリア人の宗教儀礼としての、火炎崇拝に起源を持つ。故に拝火教とも称されるゾロアスター教とも共通する同根の文化である。

仏教[編集]

仏教には釈尊入滅から約500年後に発生した大乗仏教の、中期から後期(密教)の過程でヒンドゥー教(バラモン教)から取り入れられた、と考えられている。そのため、護摩は密教(大乗仏教の一派)にのみ存在する修法である。したがって、基本的には日本の天台宗・真言宗や、チベット仏教など、密教系の宗派でのみ行われる。なお、専ら護摩を修するための堂宇を「護摩堂」(ごまどう)と称する。

護摩の種類[編集]

護摩壇に火を点じ、火中に供物を投じ、ついで護摩木を投じて祈願する外護摩と、自分自身を壇にみたて、仏の智慧の火で自分の心の中にある煩悩や業に火をつけ焼き払う内護摩とがある。

また、その個別の目的によって一般的には次の五種に分類される。

息災法(そくさいほう)…災害のないことを祈るもので、旱魃、強風、洪水、地震、火事をはじめ、個人的な苦難、煩悩も対象。

増益法(そうやくほう)…単に災害を除くだけではなく、積極的に幸福を倍増させる。福徳繁栄を目的とする修法。長寿延命、縁結びもその対象。

調伏法(ちょうぶくほう)…怨敵、魔障を除去する修法。悪行をおさえることが目的であるから、他の修法よりすぐれた阿闍梨がこれを行う。

敬愛法(けいあいほう)…調伏とは逆に、他を敬い愛する平和円満を祈る法。

鉤召法(こうちょうほう)…諸尊・善神・自分の愛する者を召し集めるための修法。

野外の護摩法要[編集]

修験道で野外において修される伝統的な護摩法要を、柴燈・採燈(灯)(さいとう)護摩という。日本の伝統的な二大修験道流派である真言系当山派では、山中で正式な密具の荘厳もままならず、柴や薪で檀を築いたために「柴燈」と称する一方、同じく伝統流派である天台系本山派では、真言系当山派の柴燈から採火して護摩を修するようになったため「採燈」と称する。

近年では、伝統的な本山派・当山派の流派には属さない寺社、また、分派、独立した宗団や密教系新宗教などでも、独自の方法と解釈により「斉燈護摩」(真如苑真澄寺)や「大柴燈護摩供」(阿含宗)、「お火焚き」「火祭り」などの別称を用いて実施されている。

神道[編集]

護摩は本来は仏教の密教の修法であるので、密教や修験道で行われるが、神道の神社の一部でも護摩が実施される。もともと神仏習合だった権現社や宮が、明治維新の神仏分離(神仏判然令)によって寺院を別の法人として改組した事例も少なくないが、現在でも神社において神職や山伏による護摩祭が続いていることがある。

愛宕神社(京都府京都市)の千日詣の夕御饌祭[2]

安井金比羅宮(京都府京都市)の春季金比羅大祭、秋季火焚祭[3]

熊野那智大社(和歌山県東牟婁郡那智勝浦町)の権現講祭[4]

八菅神社(神奈川県愛川町)の例大祭の護摩供養火生三昧の修法[5]

脚注[編集]

^ 真言宗智山派大本山 川崎大師 金剛山平間寺|ご利益|お護摩

^ 愛宕神社|千日詣

^ 安井金比羅宮|年中行事

^ 熊野那智大社|権現講祭のご案内

^ NPO法人シニアネット相模原|相模原百選|相模原の寺社・文化財|八菅神社

関連項目[編集]

火炎崇拝

加持・祈祷

大柴燈護摩供

| |||

カテゴリ: 密教

修験道

神仏習合

>>>

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Homa_(ritual)

영어번역 by 구글 [ 오류는 원문 참조 ]

호마 (의식)

무료 백과 사전, 위키피디아에서

다른 용도에 대해서는 Yagya를 참조하십시오 .

| 의 일부 일련의 에 |

| 힌두교 |

|---|

|

| 힌두교 역사 |

| 태생[보여 주다] |

| 주요 전통[보여 주다] |

| 신들[보여 주다] |

| 개념[보여 주다] |

| 관행[보여 주다] |

| 철학 학교[보여 주다] |

| 전문가, 성도, 철학자[보여 주다] |

| 텍스트[보여 주다] |

| 사회[보여 주다] |

| 기타 주제[보여 주다] |

| 힌두교 용어 해설 |

| V 티 이자형 |

공연중인 호마

에서 베다 힌두교하는 HOMA ( 산스크리트어 : होम)로도 알려져 havan는 , 불 의식에 의해 특별한 경우에 일반적으로 수행 힌두교 사제 집주인 (: 한 가정을 가진 "grihasth")에 대한. grihasth는 음식을 요리하고 집을 데우는 등 다양한 용도의 불을 지킵니다. 따라서 Yagya 제물 은 불에 직접 만들어집니다. [1] [2] 불이 제물을 파괴하기 때문에 호마는 때때로 "제물 의식"이라고 불립니다. 그러나 호마는 더 정확하게는 " 봉헌 의식"입니다. [1]불은 대리인이며 제물에는 곡식, 버터 기름 , 우유, 향 및 씨앗과 같은 물질적이고 상징적 인 제물이 포함됩니다 . [1] [3]

그것은 베다 종교에 뿌리를두고 있고 , [4] 고대에 불교 와 자이나교에 의해 채택되었습니다 . [1] [3] 관행은 인도에서 중앙 아시아, 동아시아 및 동남아시아로 퍼졌습니다. [1] 호마 의식은 많은 힌두 의식의 중요한 부분으로 남아 있으며, 오늘날의 불교 , 특히 티베트와 일본의 일부 에서 호마의 변형이 계속해서 행해지고 있습니다 . [4] [5] 현대 자이나교 에서도 발견됩니다 . [4] [6]

호마는 힌두교의 yajna 와 같은 대체 이름으로 알려져 있으며 때로는 더 큰 공공 불 의식을 의미 하거나 불교에서는 jajnavidhana 또는 goma 를 의미합니다. [3] [7] 현대에서 호마는 결혼식에서 관찰되는 것과 같이 상징적 인 불을 둘러싼 사적인 의식 인 경향이 있습니다. [8]

내용

1어원

2역사

삼힌두교

4불교

5자이나교

6또한보십시오

7참고 문헌

8외부 링크

어원 [ 편집 ]

산스크리트어 단어

homa (होम)는 "불에 붓고, 제물, 희생"을 의미 하는 뿌리 hu 에서 유래했습니다. [9] [10] [11]

역사 [ 편집 ]

호마 전통은 3000 년 이상의 역사 를 가지고 사마르 칸트 에서 일본에 이르기까지 아시아 전역에서 발견됩니다 . [4] HOMA , 모든 아시아의 변화에 제공 화재에 음식과 궁극적으로 베다 종교에 포함 된 전통에 연결되어 있음을 의식 의식이다. [4] 전통 은 아시아에서 발전한 불과 요리 된 음식 ( 파카 야냐 )에 대한 경외심을 반영하고 있으며, 베다 의 브라마나 층 은이 의식 경의에 대한 최초의 기록입니다. [12]

이너 호마, 몸을 사원으로그러므로 사람이 취할 수있는 첫 번째 음식

은 Homa 대신에 있습니다.

그리고 그 첫 번째 헌금 을 제공하는 사람은 svaha 라고 말하면서

그것을 Prana 에게 제공해야합니다 ! 그런 다음 Prana는 만족합니다. Prana가 만족하면 눈도 만족합니다. 눈이 만족하면 태양도 만족합니다. 태양이 만족하면 천국도 만족합니다.

— Chandogya Upanishad 5.19.1–2

번역 : Max Muller [13] [14]

yajñā 화재 희생은 초기의 뚜렷한 특징이되었다 śruti 의식. [4] śrauta 의식의 한 형태이다 대상물 경우 화재 의식, 신들과 여신 뭔가를 제공되는 sacrificer 및 반환에 sacrificer 예상 뭔가를 통해. [15] [16] 베다 의식이, 식용 무언가 또는 음용의 희생 제물로 구성 [17] 우유, 같은 버터 기름 도움을 신들에게 제공, 요구르트, 쌀, 보리, 동물, 또는 가치의 아무것도, 불 제사장의. [18] [19] 이 베다 śrauta 전통로 분할 (śruti 기반) 및Smarta ( Smṛti 기반). [4]

호마 의식 관습은 다른 불교 전통과 제이나 전통에 의해 관찰되었다. 필리스 그라 노프 (Pillis Granoff)는 힌두 전통의 "의식 절충주의"에 해당하는 텍스트와 함께 중세 시대를 통해 진화 한 변형에도 불구하고 관찰되었다. [4] [6] [20] 무사시 타치 카와 (Musashi Tachikawa)는 호마 스타일의 베다 제사 의식이 대승 불교에 흡수되었으며, 호마 의식은 티베트, 중국 및 일본의 일부 불교 전통에서 계속 수행되고 있습니다. [5] [21]

힌두교 [ 편집 ]_Hindu_puja,_yajna,_yagna,_Havanam_in_progress.jpg/220px-(A)_Hindu_puja,_yajna,_yagna,_Havanam_in_progress.jpg)

공물이있는 호마 제단 (위) 및 진행중인 의식

호마 의식 문법은 다양한 힌두교 전통 의 많은 산 스카라 (통행 의례) 의식에서 일반적입니다. [22] [23] [24] 힌두교의 다양한 호마 의식 변형의 핵심 인 베다 불 의식은 의식의 "양측 대칭"구조입니다. [25] 그것은 종종 불과 물, 번제물과 소마, 남성적인 불, 여성적인 흙과 물, 수직으로 위로 뻗은 불, 제단, 제물과 액체는 수평으로 결합됩니다. [25] (화덕)에 HOMA 의식의 제단 자체가 가장 자주 대칭, 정사각형, 인도 종교의 사원과 mandapas의 중심에 또한 디자인 원칙이다. [26]호마 의식 행사의 순서는 처음부터 끝까지 비슷하게 대칭 원칙을 중심으로 구성됩니다. [25] ). [25]

불 제단 ( vedi 또는 homa / havan kunda)은 일반적으로 벽돌이나 석재 또는 구리 용기로 만들어지며 거의 항상 상황을 위해 특별히 제작되어 즉시 해체됩니다. 이 불 제단은 항상 정사각형 모양으로 지어졌습니다. 매우 큰 베디 는 때때로 주요 공적인 호마를 위해 지어 지지만 , 일반적인 제단은 1 × 1 피트 평방만큼 작을 수 있으며 거의 3 × 3 피트 평방을 초과하지 않습니다. [ 인용 필요 ]

호마의 의식 공간 인 제단은 일시적이고 움직일 수 있습니다. [1] 호마 의식의 첫 번째 단계는 의식 인클로저 (mandapa)의 건설이며 마지막 단계는 해체입니다. [1] 제단과 만다 파는 성직자에 의해 봉헌되어 만트라 를 낭송하는 의식 의식을위한 신성한 공간을 만듭니다 . 찬송가와 함께 불이 시작되고 헌금이 모입니다. 희생자는 들어가서 상징적으로 물로 자신을 정화하고 호마 의식에 참여하고 신을 초대하고기도를 낭송하며 소라 껍질을 날립니다. 희생자들은 svaha 의 소리에 맞춰 찬송가와 함께 제물과 해방 을 불 에 붓습니다 . [27] 헌금과 헌금은 일반적으로 정화 된 버터 (버터 기름 ), 우유, 두부, 설탕, 사프란, 곡물, 코코넛, 향수, 향, 씨앗, 꽃잎 및 허브. [28] [29]

제단과 의식은 힌두 우주론을 상징적으로 표현한 것으로, 현실과 신과 생명체의 세계를 연결합니다. [10] 의식은 또한 대칭적인 교환, "quid pro quo"로 인간이 불의 매개체를 통해 신에게 무언가를 제공하고 그 대가로 신이 힘을 가지고 보답하고 영향력을 행사할 것이라고 기대합니다. . [10] [16]

불교 [ 편집 ]

진언 불교 승려 들은 때때로 북을 치거나 호라 가이 (하부, 소라 )를 부는 호마 의식을 수행 합니다. [30] [31]

봉헌 불의 호마 (護摩, goma ) 의식은 티베트, 중국 및 일본의 일부 불교 전통에서 발견됩니다. [5] [21]

그 뿌리는 베다 의식이며

불교 신을 불러 일으키며 자격을 갖춘 불교 사제가 수행합니다. [5] [32]

Kutadanta Sutta , Dighanikaya 및 Suttanipata 와 같은 불교 문헌의 중국어 번역 에서

6 ~ 8 세기로 거슬러 올라가면 ,

Vedic homa 관행은 부처님이 원래 교사라는 주장과 함께 부처님의지지에 기인합니다.

일본과 같은 일부 불교 전통에서이 의식에서 불려진 중심 신은 보통 Acalan ātha (Fudō Myōō 不 動 明王, lit. immovable wisdom king )입니다.

Acalanātha는 하나님의 또 다른 이름입니다 루드라 의 베다 전통에서, Vajrapani 또는 Chakdor 티벳 전통에서, 그리고 Sotshirvani 시베리아있다. [33] [34]

Acala Homa 의식 절차는 힌두교에서 볼 수있는 것과 동일한 베다 프로토콜을 따르며, 의식의 주요 부분 인 만트라를 암송하는 사제들이 불에 바치는 제물과 다른 찬송가가 낭송 될 때 신자들이 박수를칩니다. . [35]Vedic homa ( goma ) 의식 의 다른 버전은 Tendai 및 Shingon 불교 전통과 일본의 Shugendō 및 Shinto 에서 발견됩니다. [36] [37] [38]

대부분의 진언 사원에서이 의식은 매일 아침이나 오후에 행해지 며,

모든 아카리 야가 신권에 들어갈 때이 의식을 배우기위한 요건입니다. [39] 의 원래 중세 시대의 텍스트 고마 의식은 올바른 발음 제사장을 지원하기 위해 추가 일본어 가타카나로, Siddham 산스크리트어 종자 단어와 중국어에 있습니다. [40]

대규모 행사는 종종 매질, 노래, 여러 사제 포함 타이코 드럼 조가 쉘 (의 송풍 horagai 의식 초점으로 불 만다라 정도). [30] [31]

호마 의식 ( sbyin sreg) 티베트 불교와 Bön에서 널리 사용되며 다양한 대승 불상 및 탄트라 신과 연결되어 있습니다. [41]

자이나교 [ 편집 ]

호마 의식은 자이나교 에서도 발견됩니다 . [4] [6] 예를 들어, 간 타칸 의식은 수세기에 걸쳐 진화해온 호마 제사로, 제사 제물을 불로 만드는 곳에서 판캄 리트 (우유, 두부, 설탕, 사프란 및 정화 버터) 및 기타 상징적 코코넛, 향, 씨앗 및 허브와 같은 품목. [42] [43] 자이나교 의해 항 진언 산스크리트어에 해당하고, 16 세기 Svetambara 텍스트 포함 Ghantakarna 진언 Stotra가 자이나 종파 중 하나 Ghantakarna 마하비라 전용 HOMA 의식 설명 산스크리트어 텍스트이다. [42] [44]

47.348 절에있는 Jainism 의 Adipurana 는 Rishabha를 기억하는 Vedic 불 의식을 설명합니다 . [45] 힌두교 인들과 마찬가지로 전통적인 제이나 결혼식은 베다의 불 희생 의식입니다. [43] [46]

참조 [ 편집 ]

두니

홀로 코스트 (희생)

쿠 팔라 나이트

Lag BaOmer

흥청망청

참고 문헌 [ 편집 ]

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b c d e f g Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 1–3 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ Hillary Rodrigues (2003). 위대한 여신의 의식 숭배 : 해석과 함께 Durga Puja의 전례 . 뉴욕 주립 대학 출판부. pp. 329 (주 25). ISBN 978-0-7914-8844-7.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b c Axel Michaels (2016). 호모 리투 알리스 : 힌두 의식과 의식 이론에 대한 의의 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 237–248 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b c d e f g h i Timothy Lubin (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 143–166 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b c d 타치 카와 무사시 (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 126–141 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b c Phyllis Granoff (2000),다른 사람들의 의식 : 초기 중세 인도 종교의 의식 절충주의, Journal of Indian Philosophy, Volume 28, Issue 4, pages 399-424

↑ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 30, 51, 341–342 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ Axel Michaels (2016). 호모 리투 알리스 : 힌두 의식과 의식 이론에 대한 의의 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 피. 246. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

↑ Wilhelm Geiger (1998). Culavamsa : Mahavamsa의 최근 부분이 됨 . 아시아 교육 서비스. 피. 각주와 함께 234. ISBN 978-81-206-0430-8.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b c Axel Michaels (2016). 호모 리투 알리스 : 힌두 의식과 의식 이론에 대한 의의 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 피. 231.ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

^ Hu , Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, 독일

↑ Timothy Lubin (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 143–145, 148 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ Friedrich Max Muller (1879). Upanishads . Oxford University Press, 2004 년 재판. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-177-07458-2.

↑ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda , Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684 , 페이지 153, 문맥은 143–155 페이지 참조

↑ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 2–3 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b Michael Witzel(2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). 힌두교의 Blackwell 동반자. John Wiley & Sons. 피. 78.ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

↑ Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). 힌두교의 Blackwell 동반자 . John Wiley & Sons. 피. 79. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

^ Sushil Mittal; Gene Thursby (2006). 남아시아의 종교 : 소개 . Routledge. 65–66 쪽. ISBN 978-1-134-59322-4.

↑ M Dhavamony (1974). 힌두교 예배 : 희생과 성사 . Studia Missionalia. 23 . Gregorian Press, Universita Gregoriana, Roma. 107–108 쪽.

↑ Christian K. Wedemeyer (2014). 탄트라 불교 이해하기 : 인도 전통의 역사, 기호론 및 범법 . 컬럼비아 대학 출판부. 163–164 쪽. ISBN 978-0-231-16241-8.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b 타치 카와 무사시; SS Bahulkar; Madhavi Bhaskar Kolhatkar (2001). 인도 불 의식 . Motilal Banarsidass. 2–3, 21–22 쪽. ISBN 978-81-208-1781-4.

↑ Frazier, Jessica (2011). 힌두교 연구의 연속체 동반자 . 런던 : 연속체. 1 –15 쪽. ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0.

^ Sushil Mittal; Gene Thursby (2006). 남아시아의 종교 : 소개 . Routledge. 65–67 쪽. ISBN 978-1-134-59322-4.

↑ Niels Gutschow; 악셀 마이클스 (2008). Bel-Frucht und Lendentuch : 네팔 Bhaktapur의 Mädchen und Jungen . Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. 54–57 쪽. ISBN 978-3-447-05752-3.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b c d Holly Grether (2016). 호모 리투 알리스 : 힌두 의식과 의식 이론에 대한 의의 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 47–51 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

↑ Titus Burckhardt (2009). 동양 예술과 상징주의의 기초 . Routledge. 13–18 쪽. ISBN 978-1-933316-72-7.

↑ John Stratton Hawley; Vasudha Narayanan (2006). 힌두교의 삶 . 캘리포니아 대학 출판부. 피. 84. ISBN 978-0-520-24914-1.

↑ Hillary Rodrigues (2003). 위대한 여신의 의식 숭배 : 해석과 함께 Durga Puja의 전례 . 뉴욕 주립 대학 출판부. 224–231 쪽. ISBN 978-0-7914-8844-7.

↑ Natalia Lidova (1994). 초기 힌두교의 드라마와 의식 . Motilal Banarsidass. 51–52 쪽. ISBN 978-81-208-1234-5.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b Stephen Grover Covell (2005). 일본 사찰 불교 : 포기 종교의 세 속성. 하와이 대학 출판부. 2–4 쪽. ISBN 978-0-8248-2856-1.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b 폴 로렌 스완슨; Clark Chilson (2006). 일본 종교에 대한 난잔 가이드. 하와이 대학 출판부. 240–242 쪽. ISBN 978-0-8248-3002-1.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b Charles Orzech (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.).Homa in Chinese Translations and Manuals from the Sixth to 8 세기 , in Homa Variations : The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 266–268 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ John Maki Evans (2011). Kurikara : 검과 뱀 . 북대서양. 피. xvii. ISBN 978-1-58394-428-8.

^ Charles Russell Coulter; 패트리샤 터너 (2013). 고대 신들의 백과 사전 . Routledge. 피. 1113. ISBN 978-1-135-96397-2.

↑ Musashi Tachikawa (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.).일본 불교 Homa의 구조, Homa 변형 : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 134–138, 268–269 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 3, 29 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ Ryûichi Abé (2013). 만트라의 직조 : 쿠 카이와 밀교 담론의 구성 . 컬럼비아 대학 출판부. 347–348 쪽. ISBN 978-0-231-52887-0.

↑ Helen Josephine Baroni (2002). 선불교의 삽화 백과 사전 . 로젠 출판 그룹. 100–101 쪽. ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6.

↑ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 피. 338. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

↑ Michael R. Saso (1990). 탄트라 예술과 명상 : 천태 전통 . 하와이 대학 출판부. xv–xvi 쪽. ISBN 978-0-8248-1363-5.

↑ Halkias, Georgios (2016). "Siddhas의 여왕의 불 의식". Halkias에서 Georgios T (ed.). Homa 변형 . Homa Variations : Longue Durée에 걸친 의식 변화 연구 . 225–245 쪽. doi : 10.1093 / acprof : oso / 9780199351572.003.0008 . ISBN 9780199351572.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b John E. Cort (2001). 세계의 자 인스 : 인도의 종교적 가치와 이념 . 옥스포드 대학 출판부. 165–166 쪽. ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9.

^ 다음으로 이동 :a b Natubhai Shah (1998). 자이나교 : 정복자의 세계 . Motilal Banarsidass. 205–206 쪽. ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2.

↑ Kristi L. Wiley (2009 년). 자이나교의 A부터 Z까지 . 허수아비. 피. 90. ISBN 978-0-8108-6821-2.

↑ Helmuth von Glasenapp (1999 년). 자이나교 : 인도의 구원 종교 . Motilal Banarsidass. 피. 452. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

↑ Helmuth von Glasenapp (1999 년). 자이나교 : 인도의 구원 종교 . Motilal Banarsidass. 피. 458. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

외부 링크 [ 편집 ]

| Wikimedia Commons에는 Homa fire 와 관련된 미디어가 있습니다 . |

Agnihotra Firehoma

호마 요법 협회 agnihotra-online.com

탄트라 파이어

| 보여 주다V 티 이자형 힌두교 주제 |

|---|

| 권한 제어 | NDL : 00562540 |

|---|

카테고리 :Yajna

베다 세관

불교 의식

진언 불교

Vajrayana

종교 의식

불과 관련된 전통

슈 겐도

>>>

Homa (ritual)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Yagya.

A homa being performed

In the Vedic Hinduism, a homa (Sanskrit: होम) also known as havan, is a fire ritual performed usually on special occasions by a Hindu priest for a homeowner ("grihasth": one possessing a home). The grihasth keeps different kinds of fire including one to cook food, heat his home, amongst other uses; therefore, a Yagya offering is made directly into the fire [1][2] A homa is sometimes called a "sacrifice ritual" because the fire destroys the offering, but a homa is more accurately a "votive ritual".[1] The fire is the agent, and the offerings include those that are material and symbolic such as grains, ghee, milk, incense and seeds.[1][3]

It is rooted in the Vedic religion,[4] and was adopted in ancient times by Buddhism and Jainism.[1][3] The practice spread from India to Central Asia, East Asia and Southeast Asia.[1] Homa rituals remain an important part of many Hindu ceremonies, and variations of homa continue to be practiced in current-day Buddhism, particularly in parts of Tibet and Japan.[4][5] It is also found in modern Jainism.[4][6]

A homa is known by alternative names, such as yajna in Hinduism which sometimes means larger public fire rituals, or jajnavidhana or goma in Buddhism.[3][7] In modern times, a homa tends to be a private ritual around a symbolic fire, such as those observed at a wedding.[8]

Contents

1Etymology

2History

3Hinduism

4Buddhism

5Jainism

6See also

7References

8External links

Etymology[■Edit]

The Sanskrit word homa (होम) is from the root hu, which refers to "pouring into fire, offer, sacrifice".[9][10][11]

History[■Edit]

Homa traditions are found all across Asia, from Samarkand to Japan, over a 3000-year history.[4] A homa, in all its Asian variations, is a ceremonial ritual that offers food to fire and is ultimately linked to the traditions contained in the Vedic religion.[4] The tradition reflects a reverence for fire and cooked food (pākayajña) that developed in Asia, and the Brahmana layers of the Vedas are the earliest records of this ritual reverence.[12]

Inner Homa, body as templeTherefore the first food which a man may take,

is in the place of Homa.

And he who offers that first oblation,

should offer it to Prana, saying svaha!

Then Prana is satisfied.

If Prana is satisfied, the eye is satisfied.

If eye is satisfied, the sun is satisfied.

If sun is satisfied, heaven is satisfied.

— Chandogya Upanishad 5.19.1–2

Transl: Max Muller[13][14]

The yajñā or fire sacrifice became a distinct feature of the early śruti rituals.[4] A śrauta ritual is a form of quid pro quo where through the fire ritual, a sacrificer offered something to the gods and goddesses, and the sacrificer expected something in return.[15][16] The Vedic ritual consisted of sacrificial offerings of something edible or drinkable,[17] such as milk, clarified butter, yoghurt, rice, barley, an animal, or anything of value, offered to the gods with the assistance of fire priests.[18][19] This Vedic tradition split into śrauta (śruti-based) and Smarta (Smṛti-based).[4]

The homa ritual practices were observed by different Buddhist and Jaina traditions, states Phyllis Granoff, with their texts appropriating the "ritual eclecticism" of Hindu traditions, albeit with variations that evolved through medieval times.[4][6][20] The homa-style Vedic sacrifice ritual, states Musashi Tachikawa, was absorbed into Mahayana Buddhism and homa rituals continue to be performed in some Buddhist traditions in Tibet, China and Japan.[5][21]

Hinduism[■Edit]

_Hindu_puja,_yajna,_yagna,_Havanam_in_progress.jpg/220px-(A)_Hindu_puja,_yajna,_yagna,_Havanam_in_progress.jpg)

A homa altar with offerings (top), and a ceremony in progress

The homa ritual grammar is common to many sanskara (rite of passage) ceremonies in various Hindu traditions.[22][23][24] The Vedic fire ritual, at the core of various homa ritual variations in Hinduism, is a "bilaterally symmetrical" structure of a rite.[25] It often combines fire and water, burnt offerings and soma, fire as masculine, earth and water as feminine, the fire vertical and reaching upwards, while the altar, offerings and liquids being horizontal.[25] The homa ritual's altar (fire pit) is itself a symmetry, most often a square, a design principle that is also at the heart of temples and mandapas in Indian religions.[26] The sequence of homa ritual events similarly, from beginning to end, are structured around the principles of symmetry.[25] ).[25]

The fire-altar (vedi or homa/havan kunda) is generally made of brick or stone or a copper vessel, and is almost always built specifically for the occasion, being dismantled immediately afterwards. This fire-altar is invariably built in square shape. While very large vedis are occasionally built for major public homas, the usual altar may be as small as 1 × 1 foot square and rarely exceeds 3 × 3 feet square.[citation needed]

A ritual space of homa, the altar is temporary and movable.[1] The first step in a homa ritual is the construction of the ritual enclosure (mandapa), and the last step is its deconstruction.[1] The altar and mandapa is consecrated by a priest, creating a sacred space for the ritual ceremony, with recitation of mantras. With hymns sung, the fire is started, offerings collected. The sacrificer enters, symbolically cleanses himself or herself, with water, joins the homa ritual, gods invited, prayers recited, conch shell blown. The sacrificers pour offerings and libations into the fire, with hymns sung, to the sounds of svaha.[27] The oblations and offerings typically consist of clarified butter (ghee), milk, curd, sugar, saffron, grains, coconut, perfumed water, incense, seeds, petals and herbs.[28][29]

The altar and the ritual is a symbolic representation of the Hindu cosmology, a link between reality and the worlds of gods and living beings.[10] The ritual is also a symmetric exchange, a "quid pro quo", where humans offer something to the gods through the medium of fire, and in return expect that the gods will reciprocate with strength and that which they have power to influence.[10][16]

Buddhism[■Edit]

.JPG/220px-Antique_Japanese_horagi_(conch_shell_trumpet).JPG)

Shingon Buddhist priests practice homa ritual, which sometimes includes beating drums and blowing horagai (lower, conch).[30][31]

The homa (護摩, goma) ritual of consecrated fire is found in some Buddhist traditions of Tibet, China and Japan.[5][21] Its roots are the Vedic ritual, it evokes Buddhist deities, and is performed by qualified Buddhist priests.[5][32] In Chinese translations of Buddhist texts such as Kutadanta Sutta, Dighanikaya and Suttanipata, dated to be from the 6th to 8th century, the Vedic homa practice is attributed to Buddha's endorsement along with the claim that Buddha was the original teacher of the Vedas in his previous lives.[32]

In some Buddhist homa traditions, such as in Japan, the central deity invoked in this ritual is usually Acalanātha (Fudō Myōō 不動明王, lit. immovable wisdom king). Acalanātha is another name for the god Rudra in the Vedic tradition, for Vajrapani or Chakdor in Tibetan traditions, and of Sotshirvani in Siberia.[33][34] The Acala Homa ritual procedure follows the same Vedic protocols found in Hinduism, with offerings into the fire by priests who recite mantras being the main part of the ritual and the devotees clap hands as different rounds of hymns have been recited.[35] Other versions of the Vedic homa (goma) rituals are found in the Tendai and Shingon Buddhist traditions as well as in Shugendō and Shinto in Japan.[36][37][38]

In most Shingon temples, this ritual is performed daily in the morning or the afternoon, and is a requirement for all acharyas to learn this ritual upon entering the priesthood.[39] The original medieval era texts of the goma rituals are in Siddham Sanskrit seed words and Chinese, with added Japanese katakana to assist the priests in proper pronunciation.[40] Larger scale ceremonies often include multiple priests, chanting, the beating of Taiko drums and blowing of conch shell (horagai) around the mandala with fire as the ceremonial focus.[30][31] Homa rituals (sbyin sreg) widely feature in Tibetan Buddhism and Bön and are linked to a variety of Mahayana Buddhas and tantric deities.[41]

Jainism[■Edit]

Homa rituals are also found in Jainism.[4][6] For example, the Ghantakarn ritual is a homa sacrifice, which has evolved over the centuries, and where ritual offerings are made into fire, with pancamrit (milk, curd, sugar, saffron and clarified butter) and other symbolic items such as coconut, incense, seeds and herbs.[42][43] The mantra recited by Jains include those in Sanskrit, and the 16th-century Svetambara text Ghantakarna Mantra Stotra is a Sanskrit text which describes the homa ritual dedicated to Ghantakarna Mahavira in one of the Jaina sects.[42][44]

The Adipurana of Jainism, in section 47.348, describes a Vedic fire ritual in the memory of Rishabha.[45] Traditional Jaina wedding ceremonies, like among the Hindus, is a Vedic fire sacrifice ritual.[43][46]

See also[■Edit]

Dhuni

Holocaust (sacrifice)

Kupala Night

Lag BaOmer

Walpurgis Night

References[■Edit]

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Hillary Rodrigues (2003). Ritual Worship of the Great Goddess: The Liturgy of the Durga Puja with Interpretations. State University of New York Press. pp. 329 with note 25. ISBN 978-0-7914-8844-7.

^ Jump up to:a b c Axel Michaels (2016). Homo Ritualis: Hindu Ritual and Its Significance for Ritual Theory. Oxford University Press. pp. 237–248. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Timothy Lubin (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 143–166. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Jump up to:a b c d Musashi Tachikawa (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 126–141. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Jump up to:a b c Phyllis Granoff (2000), Other people's rituals: Ritual Eclecticism in early medieval Indian religious, Journal of Indian Philosophy, Volume 28, Issue 4, pages 399-424

^ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 30, 51, 341–342. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Axel Michaels (2016). Homo Ritualis: Hindu Ritual and Its Significance for Ritual Theory. Oxford University Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

^ Wilhelm Geiger (1998). Culavamsa: Being the More Recent Part of Mahavamsa. Asian Educational Services. p. 234 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-206-0430-8.

^ Jump up to:a b c Axel Michaels (2016). Homo Ritualis: Hindu Ritual and Its Significance for Ritual Theory. Oxford University Press. p. 231. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

^ Hu, Sanskrit-English Dictionary, Koeln University, Germany

^ Timothy Lubin (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 143–145, 148. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Friedrich Max Muller (1879). The Upanishads. Oxford University Press, Reprinted in 2004. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-177-07458-2.

^ Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 153, for context see pages 143–155

^ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Jump up to:a b Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

^ Michael Witzel (2008). Gavin Flood (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. John Wiley & Sons. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-470-99868-7.

^ Sushil Mittal; Gene Thursby (2006). Religions of South Asia: An Introduction. Routledge. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-1-134-59322-4.

^ M Dhavamony (1974). Hindu Worship: Sacrifices and Sacraments. Studia Missionalia. 23. Gregorian Press, Universita Gregoriana, Roma. pp. 107–108.

^ Christian K. Wedemeyer (2014). Making Sense of Tantric Buddhism: History, Semiology, and Transgression in the Indian Traditions. Columbia University Press. pp. 163–164. ISBN 978-0-231-16241-8.

^ Jump up to:a b Musashi Tachikawa; S. S. Bahulkar; Madhavi Bhaskar Kolhatkar (2001). Indian Fire Ritual. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–3, 21–22. ISBN 978-81-208-1781-4.

^ Frazier, Jessica (2011). The Continuum companion to Hindu studies. London: Continuum. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-0-8264-9966-0.

^ Sushil Mittal; Gene Thursby (2006). Religions of South Asia: An Introduction. Routledge. pp. 65–67. ISBN 978-1-134-59322-4.

^ Niels Gutschow; Axel Michaels (2008). Bel-Frucht und Lendentuch: Mädchen und Jungen in Bhaktapur, Nepal. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 54–57. ISBN 978-3-447-05752-3.

^ Jump up to:a b c d Holly Grether (2016). Homo Ritualis: Hindu Ritual and Its Significance for Ritual Theory. Oxford University Press. pp. 47–51. ISBN 978-0-19-026263-1.

^ Titus Burckhardt (2009). Foundations of Oriental Art and Symbolism. Routledge. pp. 13–18. ISBN 978-1-933316-72-7.

^ John Stratton Hawley; Vasudha Narayanan (2006). The Life of Hinduism. University of California Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-520-24914-1.

^ Hillary Rodrigues (2003). Ritual Worship of the Great Goddess: The Liturgy of the Durga Puja with Interpretations. State University of New York Press. pp. 224–231. ISBN 978-0-7914-8844-7.

^ Natalia Lidova (1994). Drama and Ritual of Early Hinduism. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-81-208-1234-5.

^ Jump up to:a b Stephen Grover Covell (2005). Japanese Temple Buddhism: Worldliness in a Religion of Renunciation. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 2–4. ISBN 978-0-8248-2856-1.

^ Jump up to:a b Paul Loren Swanson; Clark Chilson (2006). Nanzan Guide to Japanese Religions. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 240–242. ISBN 978-0-8248-3002-1.

^ Jump up to:a b Charles Orzech (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa in Chinese Translations and Manuals from the Sixth through Eighth Centuries, in Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 266–268. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ John Maki Evans (2011). Kurikara: The Sword and the Serpent. North Atlantic. p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-58394-428-8.

^ Charles Russell Coulter; Patricia Turner (2013). Encyclopedia of Ancient Deities. Routledge. p. 1113. ISBN 978-1-135-96397-2.

^ Musashi Tachikawa (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). The Structure of Japanese Buddhist Homa, in Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 134–138, 268–269. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. pp. 3, 29. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Ryûichi Abé (2013). The Weaving of Mantra: Kukai and the Construction of Esoteric Buddhist Discourse. Columbia University Press. pp. 347–348. ISBN 978-0-231-52887-0.

^ Helen Josephine Baroni (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 100–101. ISBN 978-0-8239-2240-6.

^ Richard Payne (2015). Michael Witzel (ed.). Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. Oxford University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0-19-935158-9.

^ Michael R. Saso (1990). Tantric Art and Meditation: The Tendai Tradition. University of Hawaii Press. pp. xv–xvi. ISBN 978-0-8248-1363-5.

^ Halkias, Georgios (2016). "Fire Rituals by the Queen of Siddhas". In Halkias, Georgios T (ed.). Homa Variations. Homa Variations: The Study of Ritual Change Across the Longue Durée. pp. 225–245. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199351572.003.0008. ISBN 9780199351572.

^ Jump up to:a b John E. Cort (2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. pp. 165–166. ISBN 978-0-19-803037-9.

^ Jump up to:a b Natubhai Shah (1998). Jainism: The World of Conquerors. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 205–206. ISBN 978-81-208-1938-2.

^ Kristi L. Wiley (2009). The A to Z of Jainism. Scarecrow. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-8108-6821-2.

^ Helmuth von Glasenapp (1999). Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 452. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

^ Helmuth von Glasenapp (1999). Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 458. ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2.

External links[■Edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homa fire. |

Agnihotra Firehoma

Association for Homa-Therapy agnihotra-online.com

Tantric Fire

| showv t e Hinduism topics |

|---|

| Authority control | NDL: 00562540 |

|---|

Categories: Yajna

Vedic Customs

Buddhist rituals

Shingon Buddhism

Vajrayana

Religious rituals

Traditions involving fire

Shugendō

○ [pt op tr]

>>>

'불교용어연구' 카테고리의 다른 글

| 반야등론석 (0) | 2021.01.03 |

|---|---|

| 반야등론 (0) | 2021.01.03 |

| 종경록_위키백과스크랩 (0) | 2020.12.25 |

| 근본설일체비나야파승사 (0) | 2020.12.22 |

| 현량 (0) | 2020.12.21 |